Title: The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe

Date: 1950

Publisher: Harper Collins (reprint)

ISBN: 0-06-447104-7

Length: 206 pages

Illustrations: drawings by Pauline Baynes

Quote: “Once a King or Queen in Narnia, always a King or Queen in Narnia.”

What don’t you already know about the Narnia books? I happen to be a Lewis maven but I’m sure everyone already knows something about The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, even if what you know about it is misleading. If you don’t already have the book and have any tolerance for whimsical, fantastic stories aimed at children, read this book; it’s better than the movie. That's not much of a review. To expand that thought into a full-length article I’ll add some general thoughts that may be unfamiliar to adult readers...a full-length rant.

In the 1980s his secretary and heir, Walter Hooper, published documentation that C.S. Lewis had once written the first few chapters of what was probably a very bad book, but he recognized its badness and promptly stopped. Lewis finished and published several different kinds of books; poems, which he tried to write and publish first, were the least successful, but each of his books ranks among the best of its kind.

A Disney movie version of

the Chronicles of Narnia was a bad idea; Lewis watched a few Disney movies,

during Walt Disney’s lifetime, and found nothing good to say about them. Even Lewis’s

children’s stories are too honest for

the pretty-pretty, feel-good World of Disney. These books deserve to be

read...preferably by a child in the company of an adult who can notice things

like the influence of French and Greek literature on a country whose first

royal family were called Frank and Helen.

The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe comes second in the fictional chronology but was published first. Whether it’s called “Book 1” or “Book 2” therefore depends on which edition you buy. In the first U.S. printing it’s Book 1; in the new paperback reprint it’s Book 2.

It’s a fairy tale adventure. It’s also a fairly obvious metaphor for the Christian Gospel. Children are magically transported through the wardrobe into a fantasy kingdom where they are the only real humans, where Talking Beasts and mythical creatures are governed by two competing powers, a good lion (Aslan, “Son of the Emperor Over Sea”) and a wicked witch (the “White Queen” generation or incarnation of Jadis, who represents the Evil Principle in two different forms in two other books). One of the children is alienated from the others, behaves like a brat, and falls into Jadis’s trap, from which he can only be released by the self-sacrifice of Aslan. Aslan’s transformative powers allow the children to mature from ordinary bickering schoolchildren into real, apparently full-grown, Kings and Queens, but they revert back to child form and get home in time for dinner.

Some women complain that their perception that Lewis hated women interferes with their enjoyment of his

novels. I've never had that problem, so let me expound on what I do see in his novels. I see the process

of a neurotic, confused young writer, determined to write without bigotry as a Christian despite natural

tendencies toward bigotry of many kinds, maturing into a wiser and better old writer. In

Lewis’s peculiar case, his discreet sex life is relevant.

Since several men of his generation had been deliberately miseducated to believe that they could appreciate the women they knew while despising and distrusting women as a group, and Lewis’s mother had died young and he had no sisters or other close female relatives, there was a market for his “antifeminist” remarks. Lewis was not a hater but he did sincerely believe, for much of his life, that most women were alien life forms, not very bright and more “in need of discipline” than worthy of admiration. As a Christian he tried to practice celibacy. As a young atheist...he had an intellectually intimate, physically long-distance, relationship with Arthur Greeves, who was homosexual, and Lewis himself took the shockingly “Progressive” position that homosexuality was not morally worse than other adultery. That raised some eyebrows, but nobody made a serious claim that Lewis actually had sex with another man. (He wrote in a memoir that there had been a lot of homosexual activity at one school he’d attended, but he had not been raped because he was too big to appeal to older boys who preferred smaller, more “girlish” boys. Only his estimate of the amount of homosexual activity going on—“Games and Gallantry formed the chief subjects of conversation”—was disputed.)

He lived for some time with an Army buddy’s bereaved mother, who did nothing to raise his opinion of women; some friends who knew him later in life thought that relationship might not have been altogether mother/son, but Lewis wrote of it as if it was. In the house with Lewis and his friend’s mother were the usual gaggle of hired help every middle-class British household employed in those days—even if two adults could do all their own household chores, it was considered downright immoral not to create jobs for younger and needier people—and Lewis’s diary, published as All My Road Before Me

The doomed adolescent crush on his cousin, and fantasies about fictional and mythical heroines, that Lewis noted in Surprised by Joy

As an old bachelor Lewis hadn’t been really close to his friends’ children. Little Lucy Barfield, the model for Lucy in the Narnia books, seems to have been the favorite child toward whom Lewis came as close as he ever got to feeling fatherly (he apparently never had, nor could have had, children of his own). In the Narnia books Lewis seems genuinely fond of Polly, Lucy, and Jill—who at least get each other as friends and examples—but he doesn’t try to write about them being friends.

He doesn’t write about the children’s apparently happy family lives, either, and there was a good reason for this. Between his short-lived mother, none-too-bright father, alcoholic brother, vindictive and increasingly senile adoptive mother, and sterile midlife marriage to a cancer patient, Lewis did have some experience of happy family life, but not the sort of happy family life his generation idealized so much.

So in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, Susan and Mrs Beaver are nice but shallow, Mrs Macready is the bossy old biddy (like Lewis’s friend’s mother) the children try to avoid, and although Lucy gets a brief taste of being Queen, the real Queen Regnant is Jadis, who keeps it always winter and never Christmas, turns people into stone, and is cruel to children...

Lewis and his buddies were genuinely afraid of what they thought feminism might do to women like some of their mothers, even though they saw it doing nothing of the kind to women like Sayers or Davidman. We meet wiser and more powerful women in each of Lewis’s novels, as his stunted social personality matured under Davidman’s care, but Lewis managed to write about the authentic power of a good woman only in A Grief Observed

He had all the prejudices of his generation about “Americans,” too, and Catholics (though sometimes mislabelled as Catholic by casual readers, Lewis belonged to the Church of England) and Europeans and non-White British subjects. The whole idea of a country without humans wanting and needing to be governed by humans comes straight out of Victoria’s British Empire, with a strong dose of Kipling on the White Man’s Burden. Only the fact that Lewis happened to have Irish, Scottish, Welsh, and English relatives preserved him from being, when young, an equally tedious bigot about the other kinds of British subjects; it was his good luck to be almost as much one kind of British as another. In his published writing Lewis, like Abraham Lincoln, admitted “to bigotry no sanction”—but his private speech and writing, like Lincoln’s, shows that this was very much a point of Christian discipline. Lewis wanted to write in a spirit of Christian unity and, over time, doing that guided him to see the philosophical merit even in the “heathen” religions that he described in The Abolition of Man

Because Lewis worked so hard to become the true Christian, and wise mature man, who speaks in his nonfiction and later work, he himself also had a good deal to say about his natural temperament as a Highly Sensory-Perceptive writer who had endured a lot of physical abuse (in the name of “discipline”) and social oppression. Unhappy “bright, sensitive, creative” types can become real monsters of cruelty when drugs “draw them out of their shells” of natural inhibitions, as did Hitler; they can become sadistic while sober. Lewis did, and was. In his mind a natural awareness that kindness was a more helpful “discipline” than cruelty never completely won a perpetual war with the contemporary belief that all children and animals, and other “inferiors” such as women and “the subject races,” needed to be “disciplined” at least with restrictions and punishments, if not actual beatings.

He was a good writer and teacher because he honestly, irrepressibly, enjoyed language and literature for their own sake, and was able to communicate to students the “thrill” he felt when learning a new language or finding something good about a new book. He didn't need to use punishment. His textbook on Renaissance English literature

But he never was really, completely, a nice guy. Introverts don’t have any positive emotional reaction we might call “liking” most people; introverts recovering from emotional trauma positively dislike most people. If Lewis hadn’t been a Christian he would have been a real jerk. He undoubtedly had moments of pathological jerkishness as things were. The fact that, although the Narnia books suggest that good, wise, motherly women exist even in positions of power over others as well as positions of autonomy, they don’t show us those women in action, preserves those moments for us. In the Narnia books Lucy Barfield’s teacher-friend is still struggling against an unhappy half-grown boy who fantasized about whipping his female cousin, and who probably did exploit and abuse a few working-class young women.

The nice thing about the Narnia books is that, as a girl reader (even though my feminist consciousness had been raised by a few dozen books from what was then a well stocked Women’s Studies collection at the local library), I recognized Lucy Barfield’s teacher-friend’s influence as predominant. Nobody ever needs to tell little girls that there are women they want to be like, when they grow up, and women they don’t want to be like. That is probably the first thing little girls learn about grown-up women. When little girls make up stories this contrast between desirable and undesirable female characters is likely to be noticeable; often it’s the central conflict of the stories, even if it’s encoded, as it was in some things I wrote down as a child, in descriptions of their “tastes” in dressing, shopping, or entertainment.

So when a little girl reads a story in which Lucy is probably even younger than the reader is herself, perhaps whiny and put-upon—who wouldn’t be?—but never mean, quick to forgive the others once they admit that she was right and they were wrong, tough and “game” enough to keep up with the older children, and Lucy gets to ride on a lion and dispense the healing balm and be called Queen Lucy the Valiant...whereas Jadis, who among her other nasty behaviors has punished Lucy’s scornful brother more harshly than Lucy ever even wanted to do, gets (at least the mortal body “she’s” currently using) mauled to apparent death by a lion and everybody rejoices...I don’t think any reasonable girl gets the message “Females are bad.”

What I read loud and clear, although admittedly I was fifteen when I discovered Narnia, is “Girls who forgive people who’ve snubbed them grow up to be Good Queens, or desirable women; girls who beat other children—even if they ‘deserved’ at least one good slap—beyond all reason, and then go on beating them and lashing them for miles through the snow, grow up to be Wicked Queens, or undesirable women; similar consequences would follow similar choices for boys. In this book, being lovable pays.”

As a mature scholar and specifically a student of Lewis, I now find the same message in The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, and I find it particularly and deliciously apt. Lewis did not sit down with the intention of explaining the Christian Gospel to children who liked fairy tales. He sat down with the intention of writing a nice novel-length fairy tale, which he hoped Lucy Barfield would be old enough to enjoy when he’d finished it, that began with an incongruous dream image of a lion prowling through falling snow.Fairy tales are always really about the conflict between good and evil, so the lion came to stand for good, the snow for evil, and the rest of the story fell into place, though not, Lewis admitted, while Lucy Barfield was at the age for which he’d written it.

It became, not just the Christian Gospel, but very specifically the Gospel as it Came to Lewis. The wimpy, sneaky, two-faced behavior Lewis most hated in his younger self, and went to the utmost extremes to act against even as an atheist, is the sin Aslan has to correct in Edmund. The sadistic tendencies, which were a bit harder for young Lewis to contend with, is the uncorrected sin Aslan has to destroy in Jadis. While extrojecting the sadistic fantasies of his own youth onto a female villain (Jadis’s first mortal form was “the Queen of Queens and the Terror of Charn”) Lewis was still working through his fears of extreme feminists taking over his profession, but also, at the same time, he was owning his own besetting sin and restating his commitment to overcome it.

No, he didn’t really like women, for most of his life. He didn’t like Americans. He didn’t like Jews. He didn’t like divorce, or divorced people. He didn’t like feminists. And he did sacrifice a few years of Helen Joy Davidman’s company by refusing to marry her while she was relatively healthy but her ex-husband was still alive. But then again...because he had become a radical Christian, he was able to enjoy, even more than everyone else did, the irony that when Lewis finally was able to enjoy married life, he enjoyed it with a divorced, Jewish-born, American feminist. If he never quite became a saint, the mature Christian Lewis had certainly become a different, much nicer man than the young atheist Lewis had been.

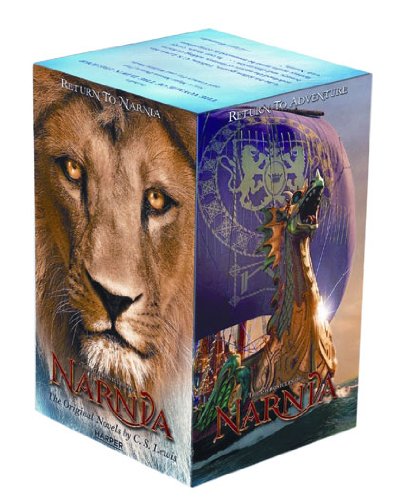

(If you're going to read the Narnia books, the position of this web site is that you should read all seven of them, and although we may be able to do better, the price will probably be $15 per boxed set + $5 for shipping + $1 per online payment. Different formats are available for different printings of these books; each set will probably ship as one odd-sized package, but no set will fit into a standard express-mail package with other books. Well, seven books for $5 shipping ought to be a good enough deal.)

No comments:

Post a Comment