https://www.patreon.com/user?u=4923804

https://www.freelancer.com/u/PriscillaKing

https://www.guru.com/freelancers/priscilla-king

https://www.fiverr.com/priscillaking

https://www.iwriter.com/priscillaking

https://www.seoclerk.com/user/PriscillaKing

You can also mail a U.S. postal money order to Boxholder, P.O. Box 322, Gate City, Virginia, 24251-0322.)

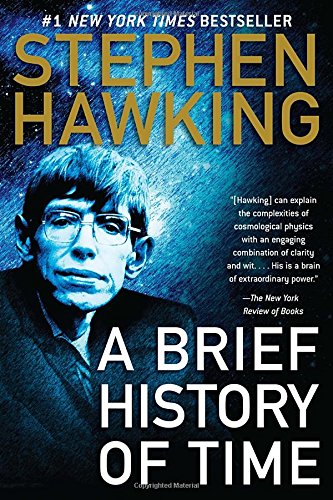

Like yesterday's poems, this short story was a contest entry that didn't win. One reason why it didn't win: although the contest sponsors' web site generally promotes science fiction and fantasy, this bit of conceptual fiction is set in more of an alternative world than a future world, although the whole fictional concept of which this story is part has always been deliberately ambiguous...The "peaceful world" has a global geography roughly similar, though not identical, to ours. It seems to be another side of our world as viewed from the fourth dimension. Is the fourth dimension time or space? I wrote these stories before Hawking wrote his Brief History of Time, when Real Physicists were still debating the matter. The fourth dimension appears in the whole story sequence as a plot vehicle that can be interpreted either way, or ignored.

Short stories tend to grow out of random thoughts, dreams...In real life I've noticed that air traffic above the Cat Sanctuary has increased dramatically in recent years. My whole family have always liked being out of sight, and (except in very damp weather) out of hearing, range from a paved road. Now the sky is a source of noise and pollution just like a paved road; I'm not pleased. And it occurred to me that in the "peaceful world," where different groups of people have agreed among themselves to adopt or reject new technology for different reasons, and they all respect one another's choices, of course flying over someone else's property would be a crime.

I erred in sharing this one with "Writers of the Future," since it does involve one of the "futuristic" cultures in the fictional Peaceful World. If we ever do evolve in the direction of peace, I think we will grow to resemble the Peaceful World, or Elizabeth Barrette's Torn World, where some people routinely use aircraft, robots, computers, etc., and others ban them. But, as mentioned in a discussion on EB's Live Journal years ago, I've always visualized the people of this world as an alien humanoid race. At the time when I started writing these stories--with my brother, who wasn't even a teenager yet--the idea of reversing the incidence of albinism and melanism seemed like a clever, satirical way to show that these people are aliens. Or, if they are our future, they're a remote and hypothetical future. Write a hundred penalty lines, Priscilla: WotF should get stories about our future; there's another'zine for tales of the fourth dimension.

(Actually the history of how Rama, specifically, got written into these stories would be a separate post; whimsy, cliches, and an obscure supplementary textbook I was studying by way of "enrichment" at school, were involved.)

I can't quite imagine our world becoming this peaceful...but we can always keep trying to cultivate this level of nonviolence and respect for others in ourselves, anyway.

Amazon link? Why not...I certainly wouldn't presume to dispute the logic that explains what the fourth dimension must really be, in...

(Fwiw, that picture just happens to make the real Stephen Hawking look like the fictional Shela Vum's father.)

1

As the four girls enter the second decade of life Kaza Mar learns that her genetic desirability score is 13. Shela Vum, with her bright blue eyes and soft dark-blue hair and clear, exquisite periwinkle-blue skin, has a score of 92. Lope Graz, whose nose is too long but whose color reaches a near-perfect purple, has a score of 81. Raza Volram, whose leaf-green skin is marred by pinkish acne, but who is expected to outgrow that, has a score of 75. Kaza’s hair, eyes, and skin barely color at all; to the extent that they do, her color is yellow. Worse than that, she can’t think of anything she would rather do, all by herself, than be with the others at school.

“Shela Vum will be an image crafter,” their teacher says enthusiastically, “and an excellent partner to Peta Rune, who has compatible talents. They should have children. Lope Graz should do well in clothing designs; her designs are beautiful. She will earn a good living, and may have children. Raza Volram might easily be a great gymnast, after which she might choose to marry and have children. Kaza Mar may have a good career as a delivery flyer. She has been scheduled for sterilization on the day 330 of the present year.”

All Rame people take a scientific approach to measurable data. Those who react emotionally to the facts of their talents and desirability are not Rame. Only through constant dedication to the science by which they live can humans live on the large continent of Rama, whose natural climates and ecosystems are not favorable to human life. Certainly Rama is not naturally favorable to Rame life, particularly. Only the discovery of flala, the coloring agent added to drinking water with the disinfectants and nutrients, could ever have allowed people born without melanin to survive on the sunniest land on the planet.

After classes on the day 23, when they receive this announcement, Shela, Raza, and Lope try to console Kaza. They will be in different classes now, of course, but they’ll remember her. They have never seen her as an ugly person. Everyone knows that an orange or yellow color in reaction to flala is a reliable indicator of many undesirable genes. Nevertheless they always rated Kaza’s personality and intelligence well in the 80s. Her life will not be as long as theirs but, while it lasts, they wish that it may be as happy, or happier.

From the day 24 forward they begin growing away from Kaza. By the day 330 they’ll be as remote as Kaza’s own parents, who are quite old for an orange and a yellow Rame, well into their thirties, and beginning to look toward death more than life.

Kaza continues to do the same gymnastic moves Raza does. Raza always did them better. Now they know that the difference is more than a matter of Raza being slightly smaller and having better rhythm. Raza will be famous, will travel far and wide, perhaps even off Rama, and eat fresh fruit every day, and live in one of those compounds where rich people’s domes are linked by covered walkways to their mates’ and children’s domes. Kaza will spend most of her time inside an airship, and will eat an orange or a mango on her weekly day of rest, and live in a small practical dome in a row of identical domes whose occupants probably never speak to each other.

Kaza continues to admire the holograms of beautiful costumes Lope displays to the class at break. The colors glow, the flounces flow, as Lope’s models dance through illusive space. Lope will probably have a selection of dresses with flowing flounces that play up her purple color. Kaza will wear yellow flightsuits, even on her day of rest, all alike and not particularly matched to her amber eyes and pale yellow skin.

Beautiful Shela and handsome jade-toned Peta begin to work as a team, discussing their stories with one another before they tell their stories to other friends. All three of them know that Kaza will be part of a twenty-person fleet, not a two-person team. Lumo Lezar, displaying empathy, allows Kaza to touch his velvety black-rose hair. Once.

Nevertheless Rama allows nothing that might be positively called cruelty or oppression of unfortunate people. Kaza will not live long, or be rich, or be loved; but she will fly. The few great forests left on Rama, the vast deserts and secret jewel mines, the massive raging rivers and the waterfalls that can be heard a mile away, will be Kaza’s daily acquaintances. She will float and dive and bound up into the air, just as Raza does, only her loops will roll on for miles. The whole sky of Rama will be her generation, the airship an ever-responsive attendant to her fast-aging body.

2

At ten Patrice Livorni, of Oxpasture town in southern Obregon, is finally allowed to hitch a plough to a meek old ox and drive it alone. Concentrating fiercely, even going so far as to string guidelines between the fences, he wants his furrows to be as straight as a full-grown man’s, and they are.

All Obregonese people, like the other civilized nations on the Phorian continent, know that a man’s vocation is to serve God through his relationship with the share of God’s earth that God appointed to his ancestors. A woman’s vocation is to crown her husband’s land with a gracious home and a healthy, well disciplined child. Some couples have a second child after marrying off the first; a few couples who marry young even manage three. To have more than one child in a house at any time appears to have been common in ancient times, but it has always produced undesirable behavior—see the fourth chapter of Genesis!—and civilized people now understand that the healthiest and best disciplined children are brought up in continuous adult company, with as little contact with other children as possible. At the very best, children together waste their time on idle games.

As a result Patrice, a healthy and well disciplined child, has only a vague general idea that other children are scattered through the district. Most of his parents’ friends are older and childless. Patrice has a cousin, an infant female he has only ever seen when she was sleeping. Occasionally, at work bees, he has worked beside other boys and tried to do a better job than they, especially when they were older.

It has never occurred to Patrice to spin silly tales, as some children do, out of the inevitable childish misunderstandings of things adults say. What he has told his parents has always been the truth.

That is why his parents are amazed, and appalled, when Patrice reports that he saw the thing that streaked through the night sky like a meteorite, but was not a meteorite. It was like an enormous wagon, only bigger, all made of polished metal, with some parts painted purple, and it was flown by a child his age with short dandelion-fuzz hair and pale skin and pale orange eyes like the cat’s, and that child waved at him.

Such children, they know, do exist; the heathen Rame on the southern continent, deprived of melanin (probably for their sins), have to stain themselves in some artificial way. The Rame also claim, though no reasonable person would believe it, to have ways to shoot themselves through the air like arrows. But the Rame, with all their faults, do at least keep to themselves.

The thing is certainly unnatural, blazing in the sky like a meteorite, returning like a comet, but not as regularly. Even the adults are, in truth, just a little bit afraid of it. Such a thing might easily crash into the earth, doing who knows what damage.

However, speculating on such things is no part of a responsible man’s business. Boaz Livorni has a quiet word with his son, in the field, about the things rational observers have found in the sky: sun, moon, stars, planets, comets, meteors. He also discusses the many peculiarities of the Rame race and the possibility that they may have learned ways to fire objects like wagons and children through the air, though he cannot imagine even a Rame surviving such a flight.

Elisheba Mother-of-Patrice Livorni quietly loads her son’s plate with extra greens at dinner.

3

On the day 126 Kaza Mar considers the ethical aspects of her now frequent night flights, and feels sure that she is doing no harm. Children are supposed to prepare for the work they will do as adults. She will fly airships. And if Raza will one day visit foreign countries, why should not Kaza see foreign countries?

Nevertheless Kaza has a vague sense that it may be best not to tell adults how she has flown over the Central Sea, on moonlight nights, and seen the islands of volcanic rock, and the orange and olive trees growing in dusty Obregon and the chalky cliffs of Debir. The flyer whose airship she borrows is her parents’ friend and has always seemed friendly to her too. And fuel...although the cost of processing must be paid by the flyers, fuel does come out of people and need to be used up. What else would people do with fuel? Sit around smelling it? Dump it, as she’s read of some unenlightened people doing in ancient times, into the ocean?

Still...adults like to make rules. When children think of things to do that seem not to break any existing rules, adults are likely to think up another ten or fifty new rules, just because they are adults. Kaza hopes, as devoutly as any Rame can do anything as unscientific as hope for anything, to grow up different from all the adults of her acquaintance in this respect.

Sometimes she wonders whether she’d like to regress back to the first decade of life, in which all children are equal. She would not. No child ever really wants to be an even younger child.

In any case Kaza does not tell her friends about her night flights. They’re kind enough not to tell her about the things they are now learning and doing in separate classes, without her. Kaza is equally kind.

She knows she cannot expect to enjoy a high level of energy for long. She has a high level of energy now. As long as she spends only one night a week flying, she needs no kla to keep her awake, and nobody complains of her being tired the next day or recommends zoma to help her sleep longer.

Kaza does, however, like sharing her secret flights with one other child, who she imagines is in some way her friend. A light sleeper, the Obregonese boy uncovers his face and looks around the empty pasture where he sleeps when Kaza approaches; he stares wide-eyed up at the airship and waves back as Kaza passes overhead. One night, she thinks, she will land the airship nearby and speak to him.

4

Boaz Livorni has a quiet word with Pastor Amadeus, who has a quiet word with Governor Laurentio, who summons Boaz Livorni to a quiet after-dinner meeting with them and other official of the church and state. Despite their courteous manners and frequent reminders that no one blames any Livorni for anything, Boaz Livorni is visibly ill at ease. He wonders whether he might feel less likely to trip over his own feet if they were walking through the grove, pruning orange trees, or might in fact be more so. All the others are wearing long black robes instead of blue-and-white twill trousers. Every one of them has had at least ten years of formal education beyond the point where Boaz Livorni stopped.

“A child,” Boaz Livorni repeats. “He thought it was a child.”

Ivor Pontio, Governor of Tunaport, hisses aloud. “Could even the Rame use a living child in such an experiment!”

“Experiment be...” Everyone knows what Laurentio would have said if fewer clergymen of rank had been present. “To shoot themselves through our air, our sky, is no less than an act of war.”

“Cousin,” Lucas Lanconi reproaches. “We have only the report of one witness, and that a ten-year-old herdboy, that they shoot anything thhrough the air. Even adults do not always easily distinguish a dream from reality, when awakened at night, and this is a herdboy.”

“One can never take a warning lightly where Rame are concerned. They have no religion. They have been known to open wars...”

“Not within recent centuries.Not since our own ancestors, in their own time of ignorance, became nvolved in...wars.” Lanconi’s whole person seems to draw back from the thought of war. They all do, but Boaz Livorni is aware of an uncharitable suspicion that Lanconi, Governor of Olivehills, may be exaggerating his sensitivity to conceal one of those secret, perverse fascinations that immorality has for some people.

“Let us pray,” proposes Bishop Barnabas, and they do; the clergymen take turns pleading with the Holy One for guidance.

After the prayer Pontio asks, “What come to your minds?”

Laurentio speaks first. “We have weapons that can intercept the type of weapon the boy has described. I propose that we use them...and send the wreckage of this missile back to Rama between two men in a rowboat.”

5

If war between civilized nations had been fewer than three hundred years behind them, no doubt the Obregonese would have been better prepared to charge their antimissile weapons, and Kaza’s last flight would have been her very last adventure.

As things are she feels two direct hits, feels her airship falter, and decides to turn and coast back to the field where the friendly wide-eyed boy sleeps. Only about fifty miles past the field, she lands with time and fuel to spare.

As she reduces speed and altitude she understands at last why adults would have disapproved of her flights. “Something might go worng”—and it has. Now she has no idea whether she can return the airship she borrowed, or whether any of these ignorant foreigners can help.

She has been studying to be able to talk to the boy. Rama uses Latin as its primary trading langue; Obregon uses French. These exotic languages resemble each other much more than either resembles Ramo; both are generally understood to have been invented, along with English, by one eccentric foreign genius. (Why did he invent three languages that looked so similar, yet were mutually unintelligible? Perhaps he was more than merely eccentric?)

On opening the door she realizes that, if the Obregonese ever do collect and use fuel, at best they leave it drying in the sun for days. In the moonlight she can discern piles of fuel lying right on the close-cropped grass. There seems no alternative, though, to stepping on the fuel-polluted ground as she checks her airship.

It is well made, with an outer shell that can absorb the shock of 98 out of 105 known types of crash. Despite an ugly hole where part of the shell was ground into the insulation she realizes that the airship could easily fly back to Rama.

As she circles back to the ladder, the wide-eyed boy bars the way. “Sta,” he says in Latin. “Stand where you are. I want my parents to see that you are real.”

He looks as if his intentions are friendly...but he pulls up the cord at the end of the step below him.

“Don’t do that!” Kaza says in Latin. It is, of course, too late. The ladder slowly retracts, loading the boy into t he airship. Startled, he almost loses his balance—but not quite—while he’s twenty cubits into the air.

He is still inside the airship when a woman runs toward Kaza, arms pumping as if she needed the long skirts gathered about her knees to help her legs move faster, shouting in her native language. As she comes closer she switches to Latin—“Release my son!”

“He will have to release himself.” The thought that the boy can easily steal her airship makes Kaza feel faint. “He sealed himself in. The control box is on the seat.”

“Patrice, Patrice,” the woman begins to scream.

Kaza looks at her and feels amazed that anyone can feel so much more emotional in this situation than she, Kaza, is feeling. When the woman pauses for breath she says, “He can’t hear us inside.”

“Stupid child! Foreign child! Who sent you here?” roars a man.

“No one sent me.” There is some sense of relief in confessing her misbehavior. “No one knew I came. No one told me I was or was not allowed to come here. I never asked.”

6

Patrice Livorni has no use for a Rame airship. After seeing that the thing that all the adults said had to be a sort of meteorite is in fact a sort of room lighted by its own glowing walls, he begins to search the glowing wall that sealed itself behind him for a way to get out again. After inadvertently raising the temperature control to a setting no human could possibly want, and starting an instructional reading of which he understands not a word, he presses a third button that causes the door to reopen and the ladder to slide down. Slowly, so slowly.

His father plucks him off the fourth step, from which he defied the foreign child, whose arms have by now been pinned in his mother’s apron. “Never touch such things! Who knows what foreign pollutants they might carry?”

By the time his feet touch the soil Patrice understands that, much as he might like to talk with the foreign child, the prudent thing to do now is ignore it.

“What we have for a governor,” his father says, “spoke of war. I would like to see his face when he learns that this was the prank of an undisciplined child.”

Patrice’s mother smiles. “Girl,” she says in Latin. (Patrice is disappointed; he had imagined that the child would be a boy.) “Have you any device we can use to send a word to your parents?”

“None,” says Kaza Mar.

This, Patrice reads in her face, is not really a lie. People who can make houses fly through the air can write without paper and ink. Very likely the girl’s means of doing that is in her flying house, not in her hands. The important part of what she means is that his parents can’t use the device.

Patrice has never used such sophistries in communicating with his parents but now, as he imagines their potential, a multitude of other sophistries suggest themselves to his mind.

7

The airship’s own distress signal, of course, awakens Shalo Shoka, vibrating his wrist, shrieking up into his face that his airship is in distress at a point in...

“O-bre...” Shalo Shoka breathes. He has never seen Obregon. No flyer has, so far as he knows. To fly over countries where people have chosen not to use airships is a crime. The thief is violating international law, and liable to punishment under the harshest of the laws of the countries involved.

Shalo Shoka will probably lose his job, and if the medical system has any say in the matter he’ll not last long without it, merely for letting his airship be stolen—but he has to report that it was stolen, and flown to one of the most resolutely anti-technology countries in the world.

8

Waking, Patrice Livorni remembers that something special happened during the night. As he begins to milk the cows he remembers the flying house in the field further west, the foreign child in his parents’ home. He still wishes it had been a boy. Girls are brought up by their mothers, boys by their fathers. Girls are taught the things boys are not taught. A boy would be like him, therefore surely a friend. About a girl, who knows?

Patrice Livorni is a well disciplined child, not as big, as strong, or as experienced as his father, but no less sensible. He allows no thought even of the foreign child to interfere with the morning’s milking and leading the cows to the right field for this day, not the field with the flying house.

9

“Pare,” says Elisheba Mother-of-Patrice Livorni to Kaza Mar. “Were you not taught even how to pare potatoes?”

“Those are potatoes?” Kaza knows potato flakes and potato starch. Neither looks much like the objects on the table before her.

“Those are potatoes...Child, what were you taught?”

“To fly airships. I can get a license at fourteen.” People like Raza Volram and Shela Vum will be schooled up to the age of twenty-five or thirty, because they are likely to live thirty or fifty years after that. People like Kaza are allowed to finish school at fourteen, because they are unlikely to be able to work after age forty. Kaza’s Latin is not up to explaining this.

“Pare lightly,” says Elisheba, marvelling that people live without potatoes.

Kaza is interested, but her mind wanders. She does not imagine Shalo Shoka in any great hurry to report the theft of his airship to corporate headquarters, but she knows she needs to return the airship.

10

At school Kaza Mar is missed. the teacher sends messages to her parents. Both reply indignantly that Kaza ought to be in school. Both are, in fact, worried.

Shela and Peta start a new story. Their characters are searching for the lost Princess Goldendawn, whom Shela has drawn with a face shaped like Kaza’s.

“A yellow princess?” says the teacher. “Do try to make your plot believable.”

11

The biggest breakfast Kaza Mar has ever eaten finally reaches an end, and she gets permission to go back to her airship to change suits. “No dawdling, Patrice,” his mother says. “Go directly to the pasture.”

“Yes, Mother.” Even one day ago, Patrice Livorni would not have made a mental note that his mother did not say “Go directly to the pasture where the cattle are to spend the day.” He will, of course, go first to the pasture with the flying house in it.

Along the way the children get their first good look at each other. Both can be said to have yellow hair. Patrice’s hair is darker, and longer, but not much. His eyes are brown; his skin is tan. Kaza’s skin is almost the color of old paper; dark glasses shield her yellowish-reddish-pale eyes from the sun.

“I’m Patrice. I’m ten years old.”

“I’m Kaza. I’m eleven.”

Patrice bows slightly, but wants the visitor to know, “I herd twenty cows and two horses. Eleven of the cows are giving milk.”

Kaza recognizes the words for domestic animals but has no idea what the animals are like. “I fly airships.”

“Is it hard to learn?”

“Navigating is as easy as steering your greshu down the street.” Patrice, Kaza sees from his face, has never used one of the transport-robots Rame children learn to steer before they learn to walk, and has seldom seen even a street. He looks more deeply impressed than she hoped. Nevertheless, she wants to admit: “Being a child is hard. If I were an adult I would have been back home by now, before the airship and I were missed.”

Patrice admits, “I’ve never talked to another child who was only one year older than I.”

“What? No school?”

“I’ve never gone to school. I do lessons while I’m out with the cattle. My parents correct and explain at meals.”

“All Rame children always go to school.” Kaza cannot imagine life without school. “We learn to steer our greshu and walk and talk at school.”

“What do your parents talk to you about then?”

“Mine don’t talk much. One is orange, and one is yellow, so they’re already old and weak. In the evenings they sleep, mostly.”

“I wonder why people who are weak would want to have children.”

“I would not know. I’m scheduled to be sterilized soon.”

“At eleven?”

“They say it hurts less at an earlier age.”

“Sorry,” Patrice mutters. (He has caught himself thinking, lately, of how all sorts of other creatures, even objects, might perceive the world. He is not sure why he’s been doing this, whether he likes it, or how he might be able to stop.) He picks up a stone and makes it skip twice on a pond. Kaza pauses to make a stone skip once before hurrying on to her airship.

At the sight of it her knees wobble with anticipation. she swarms up the ladder on all fours, not trusting her legs. “I’m sorry I trespassed in your air. I won’t again.”

“Could we write letters?” Patrice asks.

“I wish!” Kaza tugs on the cord to pull the ladder up behind her. “I will already be in trouble, being so late?”

Watching the hatch seal itself, Patrice thinks that he’d like to do unauthorized things, the way Kaza evidently does, but he doesn’t like the sound of that word “trouble.”

12

Patrice has no more strange dreams, no more extra portions of greens at dinner. His life returns to its regular routine.

Shalo Shoka’s company orders him to leave the airship at company headquarters, henceforward, and crawl to and from work in his own private greshu. On the whole he feels relieved.

Kaza is banned from school, and ordered to participate in long, boring counselling sessions, for a month. She limits her part in the counselling sessions to one-word answers to direct questions. Hints are dropped about futures less appealing than flying airships. In view of Kaza’s obvious talent and her unfitness for better-paid jobs, these hints do not go far.

Bishop Barnabas, himself, delivers the formal rebuke of the rest of the council to Governor Laurentio for having worked himself up about “war” over a child’s prank. However, since no one can prove that Laurentio’s recklessness did any damage even to the Rame airship, this rebuke likewise does not go far.

Patrice Livorni lives a long healthy life, with one wife, two children, several thousand cattle over the years, and at least three truly memorable horses. Between the ages of thirteen and thirty-nine he receives strange letters from Rama, with cards that hum tunes and paper that smells like flowers and similar extravagances. Up to the age of eleven his daughter, Cassianna, helps him reply, with long friendly letters and drawings and song lyrics, to his friend in Rama.

No comments:

Post a Comment