Hemileuca nuttalli, Nuttall's Sheep Moth, is one of the bigger and showier Hemileucas found in the Northwestern States. Along with H. hera and H. eglanterina it has sometimes been listed as a separate genus, Pseudohazis, and local variations that aren't even classified as subspecies today have been listed as species arizonensis and washingtonensis.

Photo by Ashley Mertens. Hemileucas are silk moths, Saturnids, but like to fold in their wings and try to look like oversized Noctuids. A South American species initially called Hemileuca dukinfieldi was found actually to be an oversized Noctuid.

Actually, on both Hemileucas and some Noctuids, that folded-up look may be useful, suggesting a different kind of animal to hungry birds.

It's abundantly documented online; easy to recognize and often photographed. As with the other Hemileucas, the moth's wings are rather pretty, the body is furry, the head is a little flat button at the front end of a thick shaggy thorax, and the caterpillar is yet another variety of stingingworm covered in venomous branching bristles. The natural human reaction to a stingingworm is to find a heavy stick or large stone and use it to reintegrate the animal's body into the soil, but there are people who say they'd miss the moth if it went extinct. This is a possibility at least in some parts of its range. In 2017, Canada's official agency in charge of such things, COSEWIC, declared Hemileuca nuttalli to be endangered by habitat deterioration in the Okanagan valley.

Because the Okanagan population is endangered, sites that traffic in dead bodies charge high prices for decomposing specimens of Hemileuca nuttalli. The position of this web site is that one should never pay for dead butterflies. For dead moths...well, in most of the United States nobody cares what you do with any stingingworm you happen to find. If you rear it to maturity, kill it, and sell it to someone who's not worried about tempting desperate students to wipe out local populations, your neighbors will probably be glad to have a few dozen fewer stingingworms to worry about next year. Just don't release it near any rosebushes or cherry trees.

For silk moths the Hemileucas aren't very big, nor do they produce much silk, but nuttalli looks "very large" in the northern part of its range where people don't see Cecropia, Polyphemus, or Citheronia moths. The wingspan is typically 6.5 cm but individuals have been measured between 6 and 8.7 cm, 2.3 to 3.4 inches. Females in this species are not a great deal larger than their brothers; southern individuals can grow much larger than northern ones.

The abdomen is yellow to orange, often with black stripes that may make it look like a bee to birds. Young females can look very fat and furry while they are full of eggs. Males and older females have, for an animal that lives entirely on stored fat, a slim silhouette. Smaller moths can at least drink water, but the big silk moths have no mouth parts and apparently no digestive system. The abdominal segments seem to be used only for reproduction. Most fat is stored in the thorax.

Photo by Dstathis. People like to take selfies with these moths, and you can, safely, if your hands are steady enough not to hurt the moth. In this case the moth's regressive behavior--curling up so that its bristles would face out, if it still had bristles--may serve an adaptive purpose. It's not a hornet and can't sting, but predators might not want to prove this.

Reproducing is about all these moths do. After flying up to a mile, at his top speed, to locate a female--who may be mating with someone else by the time he finds her--the male is apparently tired, and rests for the rest of the day and night. After flying about to find a host plant and laying her eggs, the female rests for a day or two, likewise. They can mate again if nothing eats them while they are recovering, but the greatest number of viable gamete cells are released after the first mating.

H. nuttalli is one of the easier Hemileucas to identify, but in California they may eat the same food and look similar to H. eglanterina annulata. (Other subspecies of eglanterina are usually more colorful, with bright pink on the forewings, especially of females.) Tuskes says the difference is that annulata always show a straight or convex black line on the hind wing, and nuttalli show a concave line. To see what he means without buying his $400 hardcover book, see Figure 1 in this PDF paper, which was a sort of outline to a section in the book. (In the specimens displayed, the annulata is bigger and darker; in the field this may not always be the case.)

Most common in Colorado, it's found as far north as southern British Columbia and as far south as northern Arizona. Caterpillars eat a variety of native plants depending on location, including bitter brush, antelope brush, currants, and snowberries. Some say they can eat pyracantha, and that they'll eat the leaves of Prunus trees or rosebushes if they can get any.

Hemileucas are funny about their food plants. As regular readers remember, if litter mates are separated and fed on different plants, they may not only look like different species but appear to be different species, not producing viable offspring if they mate with each other. (Litter mates who ate the same kind of leaves while growing up seem willing and able to reproduce with each other. No evidence of an incest taboo is reported in these moths.) The way eating an "accepted alternate" food plant can cause a Hemileuca caterpillar to grow up looking different from its parents has produced lots of confusion, and is a reason why lists of species in this genus have varied from counting six or seven species to counting more than seventy.

Diet and/or heredity seem to determine size and color variations in H. nuttalli. In some butterfly species, larger and darker individuals are reliably produced by exposure to warmer temperatures, as with the Zebra Swallowtails, where the brood that pupate in winter and fly in early spring look like a different species from the late summer brood who lay the eggs of next spring's first brood. For Hemileucas this seems not to be the case. Though southern populations of nuttalli are larger and darker on average than northern populations are, taking northern caterpillars south and letting them pupate in hot weather was found not to produce larger or darker moths.

The moths seem to have a clear sense of which kind they are. They recognize one another by scents, most of which humans can't smell. Humans have chemically analyzed the pheromones the Hemileucas use to recognize prospective mates. One of the main pheromones nuttalli rely on is also part of the distinctive scent of electra, maia, and eglanterina, raising the possibility of hybridization at least with electra and eglanterina, whose ranges could potentiall overlap with nuttalli's. They also share this scent chemical with the true silk moths in the genus Bombyx.

In fact nuttalli sometimes crossbreed with annulata, usually in captivity. In the wild they're less likely to do this because, despite looking and smelling similar and living in the same place at the same time, they are usually active at different times of day. Annulata usually fly before 1:30 p.m., and nuttalli usually fly after 1:30 p.m. Though males start flying as early as 10:30 a.m. and fly as late as 6:30 p.m., it's been estimated that fewer than one in four of these maths is active during the other species' peak flight period. In an experiment conducted by Collins and Tuskes, male eglanterina ignored female nuttalli, though male nuttalli were sometimes attracted to female eglanterina; in one of these mixed couples, the female did not start flying and laying eggs after mating, but resumed calling for another male, because the spermatophore from the male nuttalli was not successfully transferred. Other mixed couples produced far fewer offspring than conspecific couples--about a tenth as many--and their offspring did not live to maturity. Although purebred caterpillars can eat some of the same food plant,s the crossbreeds didn't eat those plants and starved themselves to death at an early age.

Collins observed that females of these species weren't very choosy, even though one female might have an opportunity to choose among several males. They look uncomfortably egg-stuffed when they climb out of their pupal shells and begin summoning males while their wings are still expanding. Normally, Collins said, they accept the first male who reaches them. Male nuttalli were eager enough to mate with a virgin female that they would get up early and fly out to meet female annulata. By the time female nuttalli were "calling," male annulata had been flying and/or mating all day and gone to rest for the night.

Hemileuca hera was also tested for willingness to hybridize with the other two species and, though the calling female was concealed from males' view, able to attract males only with her scent, hera mated only with hera. This species is more distinct in size and color and may also exude a more distinctive scent.

Speaking of hera, although nuttalli's forewings are usually light beige to yellow, they can also be white, resembling hera. However, the yellow body and hind wings identify nuttalli. Individuals with sharply contrasting black and white forewings have been photographed in Canada and all the way south to Texas, where neither hera nor nuttalli is normally found.

Two subspecies are recognized: Hemileuca nuttalli uniformis and H.n. nuttalli.

They've inspired artists.

This 18" square painting is available for $750 from https://thecopperwolf.com/products/expand-nuttalls-sheep-moth-painting-18x18 .

The life cycle of H. nuttalli, as with other northern Hemileucas, can last one or two years (or maybe more). In warm places caterpillars mature in spring, pupate in summer, and fly, mate, and lay eggs in autumn. In colder places caterpillars may spend the short summer reaching their full size as caterpillars, pupate all winter, and fly next summer. In some places different generations overlap, though the moths' flying in late summer while caterpillars feed in early summer still makes it unlikely that adult moths will ever see their own offspring.

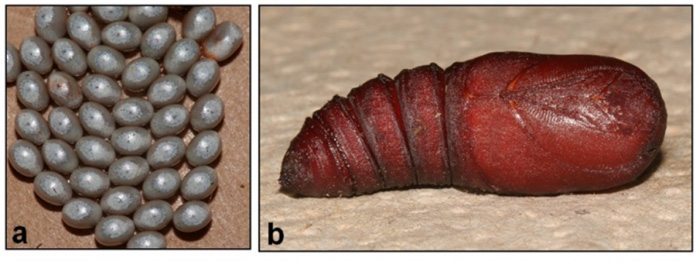

Like other Hemileucas, nuttalli hatch from eggs laid in a cluster of adjoining rings around a twig of the host plant. Eggs are greyish white and look like tiny oval beads. Eggs hatch in April or May. In Canada, where H. nuttalli is rare, its eggs have not been found and verified.

Caterpillars tend to stick close together, each one's bristles keeping the others at a healthy distance so that they don't sting one another, in the early stages of their caterpillar lives.

Photo by Kchiasson, For small animals, staying in close contact may have a survival advantage; they may look to predators like a larger, less edible animal.

When they grow big enough that each caterpillar wants to defoliate a branch of its own, they separate.

Tuskes notes that litter mates usually look alike, but caterpillars from different litters may look very different. Bristles on the upper sides of "mature" caterpillars may form flat-topped rosettes, allowing them to inflict a more painful sting because more bristle tips make contact with the same victim at the same time. Skins can have lengthwise dotted stripes or be light or dark. Bristles can be pearly gray, yellow, or black, and a commenter from British Columbia says the bristles on their stingingworms are "burnt orange.'

From the caterpillar, which is two to two and a half inches long, emerges a pupa, a little more than one inch long.

Moths fly in late summer, July to September, and are most active in the daytime. This habit causes people to think of them as butterflies and feel disappointed not to find them on lists of local butterfly species. The antennae don't end in little knobs. The insects are moths. While butterflies often fly for six weeks or longer, most moths in this species fly for less than a week.

No comments:

Post a Comment