A Fair Trade Book

The Book Review That Wanted to Be a Term Paper for a Psychology Course Not Taken

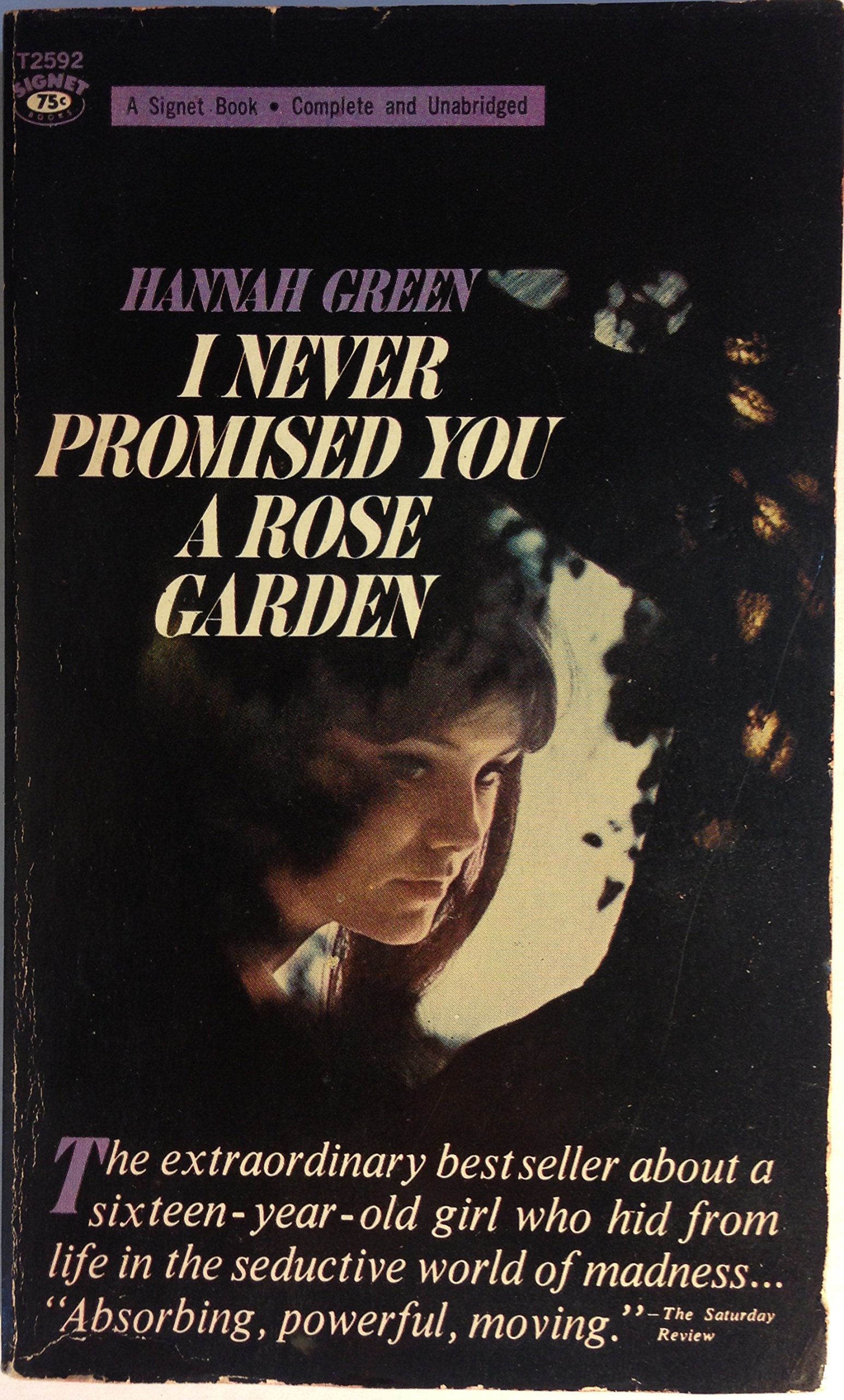

Title: I Never Promised You a Rose Garden

Author: Joanne

Greenberg as Hannah Greene

Author's web site: http://mountaintopauthor.com/

Date: 1964

Publisher: Signet

ISBN: none

Length:

Quote: “I’m bedlam as

seen by Walt Disney.”

That’s a psychotic

patient’s description of her current mood. For today’s readers, it’s also an

apt description of the whole novel.

Of all disease novels

ever written, I Never Promised You a Rose

Garden may be the best; yet it tells us only a minute fraction of what we

need to learn about Mental Health...and it seemed, when published, to promise

to tell us all.

The main character is

Deborah Blau. As a child Deborah had an

experience that was strange, possibly unique. A surgical operation left her

with what we would now call brain damage. Remembered pain, clumsiness,

dizziness, blackouts, distortion of perception, and recurrent dream images came

to dominate her perception of the world. She hardly knew when she was seeing and

hearing things as they were; she never knew for how long she’d be able to see

and hear at all. Occasionally she escaped from both pain and reality into

pleasant dream where her vertigo felt like flying. More often she sank into a

pit of blindness, helplessness, and pain.

This is not the same

disorder we now call schizophrenia, but it looked similar enough that Deborah’s

story seemed to offer hope of a cure

for schizophrenia. (A cure for schizophrenia is, of course, the holy grail of

psychiatry, as a cure for cancer is for general medicine.) Psychiatrists had to

learn the hard way that brain traumas are single experiences from which

recovery is possible, while “true” schizophrenia is hereditary and progressive.

In any case, at fifteen

Deborah makes a classic not-very-serious suicide attempt, opening a few small

surface veins, to get...back into a hospital, the last place she consciously

wants to go. But in the hospital she’s very, very lucky: after some failed

experiments using harsh, obsolete, brain-damaging drugs, doctors find the

formula that shuts off communication with the damaged part of the brain and

stops the blackouts. All psychiatric patients should be so blessed. Very few

are.

Deborah isn’t told

exactly what’s being used during the highly experimental treatment process. She’s

accustomed to having only intermittent, distorted perception of the world

outside her damaged brain, and experiences even a harsh, often abusive

psychiatric hospital as similar to home and school—better once her symptoms

begin to subside. So in the hospital she begins to develop the sort of empathy

and compassion that girls normally begin to develop around age ten. (This

capacity for empathy can initially appear as cruelty; for Deborah it

does.) She starts to make friends and even has a consciously hopeless crush on an older man.

For Deborah, recovering

from her psychotic condition is part of the same adolescence all teenagers are

going through, and so every girl, every parent, teacher, or counsellor working

with girls, and some of the guys who read this story could read into it several

things that turned out not to be true:

(1) “All You Need Is

Love.” Just caring about people, even in a detached professional way, can heal

brain damage or schizophrenia or addictions or who knows what-all, if we only

care enough. (Wrong. Her primary psychiatrist’s kindness is Deborah’s primary

source of comfort during her ordeal, but we now know that it would not have

been the primary factor in Deborah’s recovery.)

(2) So, failure to bond

with other people might be the cause of psychotic disorders. (Wrong.

Failure to bond with other people can become a source of social anxiety that

can motivate people to use drugs and damage their brains, or their whole

bodies...or a source of ordinary teen angst that can motivate people to live

through a few lonely years until they find more congenial people in grown-up

life.)

(3) And, since it’s all

about “feelings, woe, woe, woe, feelings,” people with brain damage ought to be able to receive a healthy

“sense of self” (trendy Orwellian phrase for accurate perception of external

reality) if they were treated like other people. Pain, seizures, and blackouts

could be loved away. The most bizarre behavior might be the way brain-damaged

people reacted to “feelings just like ours.”

We now know that even healthy

people perceive the world in different ways—some of us see colors and others

don’t. People like Deborah, whose emotional reactions seem “unmatching” to

anything others are perceiving, have most or all of their “feelings” about

sensations taking place inside their bodies. Until the disease causing those sensations is cured, people like Deborah do not in fact have “feelings just like

ours,” or have much energy to give them if they do.Real psychotic patients do not necessarily know or care whether we love them or not, or that we exist.

The cultural war on

introversion was underway. Some people wanted to believe that nay interest in

solitude or solitary work was a sign that people were going psychotic. Those

who admitted that that wasn’t true

still wanted to believe that people who didn’t feel a (sick, crazy, hostile, war-producing) urge to reach out and grab for

attention, to fight for control of every other face we saw, were sinfully

withholding love from other people.

I think the combination of these attitudes

and its stealth feminism (all the active characters are female) made Rose Garden a hit with female book

lovers of my generation. I know my college roommate and I used to quote Rose Garden, at length, in conversation,

as much as we did the Bible or C.S. Lewis. We didn’t understand Deborah’s

psychosis at all; like many readers we tended to overlook that part, because could we ever relate to the ordinary teenage social drama in the

story. We were fascinated, as Dr. Fried is in the book, with trying to sort out

which bits of the story are which.

Is Deborah, teen drama

queen, going to be an introvert? That’s hard to say. Though autism and schizophrenia look like the ultimate

forms of introvert social withdrawal, in fact both are produced by brain damage, independent of personality, and can happen to extroverts. Deborah seems to me,

as I reread rose Garden, to be

expressing—being trained to express—her perceptions of her disease in terms

extroverts might use to describe their experiences of mental illness. Psychotic

disorders produce social isolation by reducing people’s ability to share other

people’s experiences or, in extreme cases, even recognize other people’s

presence. Recovery from such conditions, when possible, always includes

improved ability to mingle socially with other people. The extent to which

social interaction and social withdrawal are healthy are still individual

things; for people whose talents are for solitary work, a high level of social

activity still indicates less than optimal mental health, a block in the normal, healthy, productive solitary

activity.

To some extent

Deborah’s progress involves retraining her brain, a process some best-case

psychotic patients seem to share with ordinary people who want to cultivate new

skills or habits. It’s hard to study objectively how our "internal conversations” work, but many people use internal conversations...

“That was an interesting

dream; I’d like to go back to sleep and find out...”--“Yes, and even more,

I’d like to get to work on time.”

Or: “I could use a

drink/smoke/pill...”--“Don’t go there, brain!

Go home. Call a friend.”

Or: “What that person

said/did was so obnoxious...”--“And so long ago, so

insignificant, why am I even thinking about it now? What’s my immune system

reacting to?”

We stereotype anger and

bossiness as generally male reactions to blood pressure spikes, anxiety and

depression as generally female reactions. I know people of both sexes who

typically react to blood pressure spikes in both ways. Then there are the people

who are chronically hypertensive, and chronically grouchy, domineering,

worried, or depressed...

In Rose Garden Deborah’s experience of anger seems very different from

most people’s. Early in the book she believes she’s witnessed a violent,

cowardly, despicable attack on the closest thing she has to a friend. If most of

us were watching that scene, we’d either run for help, or bash the attacker

from behind. Deborah sits there, admiring her friend’s helpless defiance, not

moving. At this point Deborah can be fairly described as insane. Later, when

she’s closer to normal consciousness but still a long way from it, she’ll

mention this episode to other people in words that suggest fear, but without

feeling fear in a normal or specific way, either Then, in what was probably a

reaction to another experimental medication, she acts out violent anger, not

feeling or remembering the incident later but obviously activated by something she would have felt as anger if she were conscious. When she starts to become sane, she has no particular problem with anger. She knows about working

for positive change, and the snarky sense of humor her family apparently

encouraged serves her well. Deborah acts out extremely problematic emotions,

yet when the physical fact of her neurological disorder is resolved, she has

only “normal, teenage” emotional problems.

One lesson to be

learned from Deborah’s anger is that psychotic patients are

completely unpredictable, likely to do things that don’t make sense even to

themselves, and to be approached very,

very carefully, if at all, because they are, in fact, very, very different from us. Not only can we not understand a

moment of genuine insanity; the person who had that moment will not, in a more

lucid moment, understand or remember it either. (Violent psychotic rage,

drunkenness, or the quiet but still psychotic moments when delirious or

overmedicated patients wake up with no memory of having come to the hospital,

have in common that if and when the patient becomes more sane s/he won’t

remember what s/he did.) The brain is a body part like any other. It can

malfunction. If our brains were to malfunction, we might do things we would not

remember or understand later, too.

Another lesson Deborah

still offers us is that we, too, can have physical feelings—that entrain our

emotional reactions, and may even stir up thoughts that seem to go with those

emotional reactions—that don’t relate to any emotions we might also be feeling.

Deborah is able to experience ordinary teenage mood swings only when she’s not

caught up in her neurological illness. Because cultural conditioning lead both

Deborah and Dr. Fried to look for some correlation between Deborah’s physical

and emotional “healing,” Deborah believes there is such a correlation and

feels gratitude for Dr. Fried’s “loving” help—yet in fact Dr. Fried does not

love Deborah, is merely kind in a more perceptive way than the other

psychiatrists, and in fact Deborah’s two separate “healings” occur on two

separate time lines in the story.

Baby-boomers and our parents wanted to

read into this story something like “Even though she doesn’t actually say it,

Deborah’s problem was that she was angry with the doctors because that surgery

hurt, and so she got lost in a tangle of fear and anger instead of feeling

love...” Wrong again. Deborah is only able to feel tangled up in the desire,

fear, insecurity, and self-consciousness all teenagers feel after she’s able to

carry on conversations without blacking out.

So many readers of Rose Garden (and other sweet hopeful

stories about recovery from Mental Illness)failed so resoundingly to love

anybody out of anything, even addiction...No amount of

empathy or love ends a pain-induced nightmare, much less a disease-induced

trance. People had to walk their own lonesome valleys by themselves, as Deborah

does in the first half of the novel. Survivors should feel no guilt about the

loved ones love couldn't“reach,” whether their primary disease

condition was located in the brain or in the pancreas.

Even together, love...we couldn't have saved Deborah, if she hadn't been that rare and lucky patient whose brain damage could be controlled after the fact by medication. That said, Deborah

does still have to retrain her brain.

For most of us,

thinking about things other than our immediate physical environment is

harmless. For some people, as Bruno Bettelheim demonstrated, imagining better

environments than the one physically surrounding us can save our sanity. For

some psychotic patients who’ve recovered, though, there are specific thoughts, “fantasies” for Freud’s and Jung’s patients, “stinking

thinking” for addicts, self-pity or nostalgia or shame or blame or other mood

triggers for people with mood disorders, that they need to avoid. Deborah has to give up, at least temporarily,

focussing on the relatively pleasing mental image, the sensation of “flying”

and communion with imaginary friends, that have been associated with the less

painful symptoms of her disorder. For her, it’s just possible that a fantasy of

“flying with the gods” of her damaged brain might indeed trigger another

relapse “into the Pit.” People who’ve developed some degree of control over

schizophrenic conditions have reported similar effects. Deborah has to make a

conscious decision that it’s safer to think about ordinary human friends than

even her best imaginary friend, the enticing false “god...who was none other

than Milton’s Satan.”

So “love” is some part

of what she needs, after all. Even faith is some part of what she needs, although Deborah’s faith is Jewish

and she backs away from religious thoughts, once describing her religion as

“Newtonian.”

Read merely as its

text, Rose Garden has a hopeful

ending. If it’s autobiographical, as some suspect, it has one of the happiest endings a novel

ever had: Greenberg has enjoyed a long and successful career (and no, she’s not

had to give up all use of her

imagination—she’s a novelist). If Deborah’s story was part of hers, then

Deborah was later able to use her imagination, safely, to write insightful

realistic novels about people who are “outside the mainstream” in a multitude

of ways—though none of those novels was as great as Rose Garden.

One reason why

psychological research has not focussed more on this kind of best-case stories

is that they still tend to be “statistical outliers.” Still, it would be

interesting to study the histories of sane people living with major brain

damage in the light of modern, neurochemical-focussed psychology, to find out

more not only about the specific neurotransmitters involved in the cure or

management of their symptoms but also about the limited, but still significant, roles of cognitive retraining and social bonds in recovery.

This book has been reprinted many times and is available in several different editions. If you're not particular about one of the harder-to-find editions, it can be bought here as A Fair Trade Book for $5 per book, $5 per package, and $1 per online payment. (This payment system is explained in the Greeting post.) From that we'll send $1 per copy sold to Greenberg or the charity of her choice. Seven more books of the size of the cheaper, pocket-sized paperback should fit into one $5 package, making prices competitive with ordering directly from Amazon, and you could select books by seven other living writers and send payments to encourage all eight of them.

No comments:

Post a Comment