A Fair Trade Book (but for how long? Buy it now!)

Title: The Woman’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets

Author: Barbara G. Walker

Date: 1983

Publisher: Harper Collins

ISBN: 0-06-250925-X

Length: 1121 pages

Illustrations: black-and-white photos

Quote: “History was written by church historians who claimed the church ‘took no part in the corporal punishment of heretics.’...Magistrates were commanded to carry out the death penalty by the dire threat of excommunication and consequent arrest.”

Wow. Eleven hundred fact-packed pages from a world-class research fanatic...wow I said.

Yes, that’s the “wow” of mixed feelings. So much went into this book. It’ a huge book. the encyclopedia format organizes material into short essays, alphabetized by topics; most are about one page long, many are less, and some are ten or twelve pages. Walker sifted out the freshest, juiciest, most pungent facts from literally hundreds of scholarly books, most of which you and I don’t have even at our local public libraries, to make each essay a pithy, memorable read.And ooohhh, how she makes me covet those books that she read and I’ve not...because I have read about a third of her sources, and I don’t think she’s done them justice. To Christianity, against which she and her audience were in active rebellion, she’s not even tried to be fair.

There. How many reviewers would say that about a book of this magnitude? In the 1980s most reviewers just wittered and waffled and murmured admiringly and hoped they sounded as if they’d read the whole Encyclopedia, without actually claiming they had. Most hadn’t.(Fair disclosure: I discovered this book in 1988 and had read the whole thing, once, by 1991. Encyclopedias aren’t meant to be read from cover to cover.) Others just made unsympathetic noises about a fact they didn’t need this book to tell them: Walker is a Secular Humanist, left-leaning, feminist agnostic.

Enough unsympathetic noises already! Secular Humanist left-leaning feminist agnostics made most of the noise, took most of the heat, and allowed quieter, more “conservative” feminists to look good while opening the doors through which my generation strolled, in the 1980s. We owe Walker, and Mary Daly and Germaine Greer, as much as we owe the women we’ve taken as role models.

Now for the big secret...What Secular Humanist agnostics have been saying for more than a hundred years is that our “Abrahamic” (Jewish, Christian, or Islamic) religious tradition is not as unique as some people like to think.

Actually, if you were paying attention, you might have remembered that the Bible writers admit that Abraham’s prophetic message was to reform an existing tradition that he and the Bible writers considered corrupt. (So, for that matter, was Muhammad’s.) The messages that God was One, that God wanted people to behave decently toward one another, and that God preferred “sacrificial” barbecues of sheep or goats to barbecues of humans, are known to have been preached by others as well as Abraham. The Bible mentions Melchizedek; African tradition mentions a visionary woman called Jezanna; in India, during the Old Testament period, Buddha was preaching peace and vegetarianism; the ancient Romans had no history or collective memory of when their culture had renounced human sacrifice. One of Walker’s Christian sources accurately says that it’s a pity that much of the history of world religious thought was either never written down into history, or else deliberately purged out of history. It would have been interesting to know who else had reformed (and/or corrupted) other cultures in which ways...

And what was this corruption? The Golden Bough documented several forms of it. (Oh how I wish I’d ever had a complete, unabridged Golden Bough.) The White Goddess

documented several forms of it. (Oh how I wish I’d ever had a complete, unabridged Golden Bough.) The White Goddess  fitted pieces together to form a plausible, though speculative, picture of a viable but extremely corruptible religion. The Woman’s Encyclopedia begins by treating The White Goddess as fact, which it isn’t, rather than well-informed speculative fiction, and by presupposing that all Bible and church history has been falsified, which is unprovable. On this kind of theory, it might seem that the whole ancient world was dominated by a universal faith in a Supreme Goddess whose Mysteries were celebrated by ritually breeding the local beauty queen to the local athletic hero, then killing the young man, duly mourning his untimely death, eating his flesh, and praying for his rebirth in the form of a son next winter.

fitted pieces together to form a plausible, though speculative, picture of a viable but extremely corruptible religion. The Woman’s Encyclopedia begins by treating The White Goddess as fact, which it isn’t, rather than well-informed speculative fiction, and by presupposing that all Bible and church history has been falsified, which is unprovable. On this kind of theory, it might seem that the whole ancient world was dominated by a universal faith in a Supreme Goddess whose Mysteries were celebrated by ritually breeding the local beauty queen to the local athletic hero, then killing the young man, duly mourning his untimely death, eating his flesh, and praying for his rebirth in the form of a son next winter.

In practice, a world of scattered illiterate tribes was unlikely ever to have had a universal belief in anything. People worked out different balances of power in different places. Several events that weren’t documented, or weren’t accurately documented, except in crude sculptures or painting, may well have been conflicts between male and female leaders or cults. Anthropologists have speculated, but nobody has proved and most anthropologists no longer believe, that there was a “Golden Age of Gynecocracy”; what is known is that some ancient cultures were matrilineal and matrilocal and to some extent even partly matriarchal. This became important only in the nineteenth century, when Auguste Comte ’s fantasy that all women were naturally suited to being “angels in the home” was tested and found unworkable as a basis for public policy. It became necessary to refute the claims that “women couldn’t” do this or that. For every job the masculinists wanted to claim women couldn’t do, including combat, there is historical evidence that some women, somewhere, have done it; just like a man and better than some. There were and still are jobs that nursing mothers shouldn’t do. In a healthy society, where women’s fertile years last less than half as long as most women’s active adult lives do, most women are not nursing mothers.

’s fantasy that all women were naturally suited to being “angels in the home” was tested and found unworkable as a basis for public policy. It became necessary to refute the claims that “women couldn’t” do this or that. For every job the masculinists wanted to claim women couldn’t do, including combat, there is historical evidence that some women, somewhere, have done it; just like a man and better than some. There were and still are jobs that nursing mothers shouldn’t do. In a healthy society, where women’s fertile years last less than half as long as most women’s active adult lives do, most women are not nursing mothers.

Most of the preliterate cultures we know about had fertility goddesses, often identified with animal or plant life. However, the extent to which these goddesses were actually worshipped varied, and in most of them the idea of a goddess did not raise the status of most women at all; in fact, when women worshipped goddesses, it seems usually to have been because they were considered too inferior to be tolerated in the cults of the male gods. Walker ignores that inconvenient truth throughout the Woman’s Encyclopedia, which leaves her celebrating many victories like that of the cult of Athena in Athens: the women got the city named in honor of their goddess, yes, and in exchange they renounced voting and civil rights...did they really negotiate this? How reliable were Athenian historians?

Walker tends to favor the assumption that all stories the ancient world preserved as "sacred scripture" were just revised myths, even when they've been documented by contemporary outside sources. Josephus, who wasn't a Christian, had heard something about Jesus, and Tacitus, who wasn't Jewish, had heard something about Moses, but Walker seems to prefer to believe that Moses may not have been a real man at all. This has to be considered a weakness. Both the authenticity of ancient documents and the accuracy of their translation force any serious historian to admit some doubts about them, but the serious historian should doubt all of them impartially.

If anything, the plausible story, like "I wrote this book all by myself at the age of 75," may be more likely to be an outright lie than the mythical story, like "St. Christina the Astonishing, after being dead and laid out for burial, flew up into the rafters..." This would be "flew" in the sense of "fled," and if the poor girl came out of a mild concussion able to run, I don't doubt for a minute that run was what she did! But a lot of things written in the names of well-known people, in their old age or after their death, were actually the work of their students or admirers...

Rereading my way through this book, I found myself wanting to collect the source materials and rewrite the whole dang thing in a way that sounds less bigoted. I almost did that in this review. I'll spare you. Let's just say that, though Walker was an old lady and used tasteful foreign-scholarly-sounding words, the "adult content" of the Woman's Encyclopedia is extremely high and there's an intention to pique, if not goad, even sympathetic female Humanist readers. You won't read this book in a hurry and you probably won't like several parts of it. Sex, violence, and cannibalism were in fact parts of some ancient religions, and in this book they're presumed to be more important parts of more ancient religions than they probably really were. Nevertheless I think the book is valuable.

The essay on the Inquisition is unpleasant reading. The Inquisition was a horror story of greed, murder, rape, torture, and blasphemy--and it's true--and it went on for more years than the Nazi Holocaust; it was the mass murder Hitler would have committed if able, rather than the mass murder he did commit. And every Christian needs to read at least one long essay that details a few of the atrocities committed "to the greater glory of God" by so-called religious men, just so we'll understand that repeating the name of Jesus does not in any way stop evildoers from doing evil.

The essay on Jesus, in which Walker assumes that everyone is familiar with the Gospel story and that Graves' speculative novel King Jesus is more likely to be closer to the facts than the Gospels are, should be a finalist in any collection of "Worst Essays." Whether you believe that humanity needed a spiritual Savior or not, or that Jesus was it or not, discarding history in favor of a second-rate novel written two thousand years after the fact is just not the way to write a serious historical essay. Walker had her reasons for writing to her audience as she did; I say the result is still a bad essay, not even an enjoyably provocative read, and can safely be skipped. Walker was using "junk" and "bunk" to "debunk."

Worldwide, the ideas of resuscitation, resurrection, or reincarnation are expressed in words that suggest getting up; everyone has seen someone fall down and get up again. Visions of the resurrected or reincarnated going up have featured ladders or stairways in every culture that has invented such things.

Walker tends to favor the assumption that all stories the ancient world preserved as "sacred scripture" were just revised myths, even when they've been documented by contemporary outside sources. Josephus, who wasn't a Christian, had heard something about Jesus, and Tacitus, who wasn't Jewish, had heard something about Moses, but Walker seems to prefer to believe that Moses may not have been a real man at all. This has to be considered a weakness. Both the authenticity of ancient documents and the accuracy of their translation force any serious historian to admit some doubts about them, but the serious historian should doubt all of them impartially.

If anything, the plausible story, like "I wrote this book all by myself at the age of 75," may be more likely to be an outright lie than the mythical story, like "St. Christina the Astonishing, after being dead and laid out for burial, flew up into the rafters..." This would be "flew" in the sense of "fled," and if the poor girl came out of a mild concussion able to run, I don't doubt for a minute that run was what she did! But a lot of things written in the names of well-known people, in their old age or after their death, were actually the work of their students or admirers...

Rereading my way through this book, I found myself wanting to collect the source materials and rewrite the whole dang thing in a way that sounds less bigoted. I almost did that in this review. I'll spare you. Let's just say that, though Walker was an old lady and used tasteful foreign-scholarly-sounding words, the "adult content" of the Woman's Encyclopedia is extremely high and there's an intention to pique, if not goad, even sympathetic female Humanist readers. You won't read this book in a hurry and you probably won't like several parts of it. Sex, violence, and cannibalism were in fact parts of some ancient religions, and in this book they're presumed to be more important parts of more ancient religions than they probably really were. Nevertheless I think the book is valuable.

The essay on the Inquisition is unpleasant reading. The Inquisition was a horror story of greed, murder, rape, torture, and blasphemy--and it's true--and it went on for more years than the Nazi Holocaust; it was the mass murder Hitler would have committed if able, rather than the mass murder he did commit. And every Christian needs to read at least one long essay that details a few of the atrocities committed "to the greater glory of God" by so-called religious men, just so we'll understand that repeating the name of Jesus does not in any way stop evildoers from doing evil.

The essay on Jesus, in which Walker assumes that everyone is familiar with the Gospel story and that Graves' speculative novel King Jesus is more likely to be closer to the facts than the Gospels are, should be a finalist in any collection of "Worst Essays." Whether you believe that humanity needed a spiritual Savior or not, or that Jesus was it or not, discarding history in favor of a second-rate novel written two thousand years after the fact is just not the way to write a serious historical essay. Walker had her reasons for writing to her audience as she did; I say the result is still a bad essay, not even an enjoyably provocative read, and can safely be skipped. Walker was using "junk" and "bunk" to "debunk."

Worldwide, the ideas of resuscitation, resurrection, or reincarnation are expressed in words that suggest getting up; everyone has seen someone fall down and get up again. Visions of the resurrected or reincarnated going up have featured ladders or stairways in every culture that has invented such things.

|

| The original "Stairway to Heaven," posted on Wikipedia By Pvasiliadis - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2386101 |

A sixth or seventh century book, probably pseudonymous as books written by members of the privileged classes were expected to be, was called Klimax (Greek), or Scala Paradisi (Latin), which can be translated as “The Ladder to Heaven” or more recently as “The Ladder of Divine Ascent ”; its author is remembered as Johannes Climacus, John of the Ladder. The only documentation of Brother John is a vague undocumented book allegedly written by a fellow monk, also undocumented. Johannes Climacus can fairly be described as an obscure or shadowy writer. Walker rushed to theorize that he was “a bogus saint” invented for the purpose of sneaking Tantric Buddhist thought, in which “the stairway to heaven” has a different meaning, into the monastery.

”; its author is remembered as Johannes Climacus, John of the Ladder. The only documentation of Brother John is a vague undocumented book allegedly written by a fellow monk, also undocumented. Johannes Climacus can fairly be described as an obscure or shadowy writer. Walker rushed to theorize that he was “a bogus saint” invented for the purpose of sneaking Tantric Buddhist thought, in which “the stairway to heaven” has a different meaning, into the monastery.

Ahem. If “The Stairway to Heaven” had communicated Tantric ideas about using the act of marriage as a meditative practice, to celibate monks, it would not have been dutifully copied by hand for all those years, nor would Johannes Climacus have been canonized as a saint. Men with sex on their minds can find an erotic double meaning for anything, but we can be reasonably confident that The Ladder of Divine Ascent does not generally suggest Tantric ideas to normal minds. Using this kind of logic, some future writer might reasonably affirm that the writer known as “Barbara Walker,” author of a book called The Crone , was obviously the same person as the long-distance walker known as “Granny D.” Bunk, I say, and bosh, and also twaddle!

, was obviously the same person as the long-distance walker known as “Granny D.” Bunk, I say, and bosh, and also twaddle!

Ahem. If “The Stairway to Heaven” had communicated Tantric ideas about using the act of marriage as a meditative practice, to celibate monks, it would not have been dutifully copied by hand for all those years, nor would Johannes Climacus have been canonized as a saint. Men with sex on their minds can find an erotic double meaning for anything, but we can be reasonably confident that The Ladder of Divine Ascent does not generally suggest Tantric ideas to normal minds. Using this kind of logic, some future writer might reasonably affirm that the writer known as “Barbara Walker,” author of a book called The Crone

So, do young women still need this outrageously biased book? I say they do. We can afford to keep more recent memories of more pleasant relationships on the tops of our mental files. For every woman writer who’s been discouraged by a sexist priest or pastor, we can find a writer like Anne Lamott or Kathleen Norris

or Kathleen Norris  who’ll testify that churchmen not only encouraged her writing but were also supportive of her needs for specifically male help—raising a son, or caring for a disabled husband. We cannot afford to forget the hate. We need that long, vitriolic essay about the Inquisition. When we come to the quote translating Hitler’s words as “As a Christian, I...” we can afford to say that Hitler was probably lying (as he advocated doing in Mein Kampf), also claimed to have rejected Jesus in favor of the “stronger” German Pagan “gods,” and in any case was never representative of Christians. We need to remember the Inquisition as proof that the name of Jesus, or even the exercise of copying Bible texts, does not keep people from being greedheads or even sadistic sociopaths.

who’ll testify that churchmen not only encouraged her writing but were also supportive of her needs for specifically male help—raising a son, or caring for a disabled husband. We cannot afford to forget the hate. We need that long, vitriolic essay about the Inquisition. When we come to the quote translating Hitler’s words as “As a Christian, I...” we can afford to say that Hitler was probably lying (as he advocated doing in Mein Kampf), also claimed to have rejected Jesus in favor of the “stronger” German Pagan “gods,” and in any case was never representative of Christians. We need to remember the Inquisition as proof that the name of Jesus, or even the exercise of copying Bible texts, does not keep people from being greedheads or even sadistic sociopaths.

Talking of Hitler, pop singer Erykah Badu recently tried to cite “finding good things to say about Hitler” as an example of her Humanist philosophy (“Baduizm”) that we should look for good things to say about everybody. Between an unsympathetic interviewer and an apparently hung-over mood, Badu failed dramatically to find a good thing to say about Hitler. Well, he did have an unhappy childhood, possibly because his sociopathic tendencies were noticed and/or because they ran in his family; lots of people have unhappy childhoods and don’t become murderers. And Hitler was on “performance-boosting” drugs, which should be remembered as a warning to anyone who feels tired or depressed enough to need feel-good stimulants stronger than caffeine. But I think it’s very important to remember one set of “good” things about Hitler. He was a sociopath who manipulated people with Big Lies, and admitted it; but he was a smart, successful sociopath. He implemented evil policies by appealing to people’s good wishes. His Big Lies appealed to people all over the world in the 1930s, and when anyone else is spouting them they still appeal to people today. People still want to believe that “we” can make everyone happy and healthy and orderly...and that’s where Nazional Sozialism starts.

If we really want abominations like banning all women, or all Jews, or all members of some other group, from jobs or from cities or from entire countries, to happen Never Again, we must remember that they start when someone grabs control of society by promising to make everything better for everyone. Auguste Comte would probably not have liked Adolf Hitler, if they’d met, but Comte’s line of thought led directly to Hitler’s. And it always has; and it always will.

Walker’s Encyclopedia pries Christian’ hands away from our eyes and ears, and forces us to remember that allowing the Bible or the life of Jesus to influence our thoughts about “making everything better” does not protect those thoughts from exploitation of the most corrupt, degenerate, selfish, greedy, and sadistic kinds. “Make” is the key. The moment we think about making anyone else do anything, as distinct from encouraging or empowering them to do it if they so choose, we begin to enable evildoers to harm the people we fantasize about helping.

Male bigotry is undeniable in the history of all of the “Abrahamic” religions—and of the others. The New Testament documents that women, and specifically enslaved women, flocked to Christianity because the teachings of Jesus were so liberating for them, compared with the rules of Greco-Roman Pagan society. Many were recognized as teachers, “prophets,” “deacons,” and “apostles” (the apostolic church had no priests, claiming Jesus as their one High Priest). St. Paul’s eye must have twinkled with irony when he wrote to St. Timothy, “I suffer not a woman to teach or usurp authority over a man,” because both Paul and Timothy had been taught by Christian women. The “authority” of Eunice, Lois, Prisca-and/or-Priscilla, was not “usurped” from men; it was obviously understood as their own gift from God.

Only one female Christian teacher was denounced as “that woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophet.” Jezebel was historically the name of a queen of Israel who was greatly hated for reintroducing human sacrifice and introducing the doctrine of “eminent domain” into that country. It seems unlikely that parents named a daughter, or that women named themselves, in honor of her. More likely “that woman Jezebel” was one of those incompletely converted members of Pagan cults that reacted to the Gospel story with, “Ah yes, we have that kind of ritual too...his tortured body disappeared and then reappeared alive and well, you say? And he had a follower called Thomas, which means ‘twin’—that would have been His twin? And did you really send St. Thomas off to India, or did you sacrifice him next?” In any case, later generations of Bible scholars ignored the many women who were advised to teach “with (the sign of) authority on her head, for the sake of the message” (angelion means message), and even the ones who came to Christian meetings “to learn in silence, with due subjection,” and fixated on the one woman who had apparently gained authorization to teach and started teaching the message all wrong. That happened, and if Christians find it “hurtful,” once again they should accept the sting as good for them.

Only one female Christian teacher was denounced as “that woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophet.” Jezebel was historically the name of a queen of Israel who was greatly hated for reintroducing human sacrifice and introducing the doctrine of “eminent domain” into that country. It seems unlikely that parents named a daughter, or that women named themselves, in honor of her. More likely “that woman Jezebel” was one of those incompletely converted members of Pagan cults that reacted to the Gospel story with, “Ah yes, we have that kind of ritual too...his tortured body disappeared and then reappeared alive and well, you say? And he had a follower called Thomas, which means ‘twin’—that would have been His twin? And did you really send St. Thomas off to India, or did you sacrifice him next?” In any case, later generations of Bible scholars ignored the many women who were advised to teach “with (the sign of) authority on her head, for the sake of the message” (angelion means message), and even the ones who came to Christian meetings “to learn in silence, with due subjection,” and fixated on the one woman who had apparently gained authorization to teach and started teaching the message all wrong. That happened, and if Christians find it “hurtful,” once again they should accept the sting as good for them.

However the male bigotry against the early Christian “prophetesses” was by no means confined to Jewish-Christian scholars like Paul. It came from Jewish rabbis, who had determined, while enslaved in Babylon, that teaching women the Torah was “the same as teaching them prostitution” (and in Babylonian culture that might even have been true). It came from Pagan slavemasters, like the owners of the wretched girl who was “possessed” to screech mockingly in the street that Paul was a servant of God teaching the right way to salvation, who weren’t at all pleased when the girl miraculously recovered apparent sanity. (Many Pagan cultures exploited brain-damaged people to serve as mystical oracles—often females, since brain-damaged men could be used for heavier work—so it’s plausible that this slave had been drugged, and “miraculously” sobered up.) Most of all the bigotry came from Roman overlords who basically resented that Christians were refusing to pay the cost of daily animal sacrifices in the name of the emperor’s supposedly deified ancestors.

“Christians were arrested for civil crimes,” Walker says. Yes—they were at least accused of civil crimes, although encouraging people not to pay for the Pagan animal sacrifices was the main charge. Beyond that, Christians were also accused of lots of other things. Forensic evidence was unknown, so if you knew a ruling official’s prejudices, you could commit murder, arson, theft, and worse, and walk, by claiming to have seen someone against whom the ruler was prejudiced doing those things. And yes, although some of the “virgin martyrs” almost certainly were based on fragments found near a place where somebody wanted to build a church, much later, refusing to consent to a marriage arranged by Pagan parents was punishable as sedition too. I have to wonder how Walker managed to overlook what Kathleen Norris  found so obvious, ten years later: some of the “virgin martyrs” probably were real girls, and probably were killed for the “crime” of resisting rape—by the men to whom their greedy parents had sold them in marriage, or by men in the Roman government after the girls had been accused of crimes. (Jailers traditionally claimed a “right” to rape any girl, or any boy for that matter, they happened to fancy.)

found so obvious, ten years later: some of the “virgin martyrs” probably were real girls, and probably were killed for the “crime” of resisting rape—by the men to whom their greedy parents had sold them in marriage, or by men in the Roman government after the girls had been accused of crimes. (Jailers traditionally claimed a “right” to rape any girl, or any boy for that matter, they happened to fancy.)

If Walker bashed Christianity, Judaism, and Islam alike, what did she positively believe and teach? Nothing in the Encyclopedia; Women’s Rituals  was a separate book. Any feminist group that drew on, or cult that might have followed (if one did follow) Walker’s work, would have been essentially a Humanist, activist, consciousness-raising group who used images, symbols, perhaps the I Ching

was a separate book. Any feminist group that drew on, or cult that might have followed (if one did follow) Walker’s work, would have been essentially a Humanist, activist, consciousness-raising group who used images, symbols, perhaps the I Ching  and the Tarot

and the Tarot , and surely beautiful stones

, and surely beautiful stones if they happened (as Walker had) to have collected some, as starting points for group discussions and perhaps demonstrations. (I’m not sure who named “Lilith Fair”; the slogan “Take back the night” can be positively traced to Walker’s work.) Walker was opposed to letting women’s groups deteriorate into spiritualism, in the name of “women’s spirituality.” She wanted them to remain rationalist and Humanist, appreciating traditional archetypes for their psychological and artistic value. The litany she proposed for each meeting of such groups was “Who is our Goddess? Behold, she is ourselves.”

if they happened (as Walker had) to have collected some, as starting points for group discussions and perhaps demonstrations. (I’m not sure who named “Lilith Fair”; the slogan “Take back the night” can be positively traced to Walker’s work.) Walker was opposed to letting women’s groups deteriorate into spiritualism, in the name of “women’s spirituality.” She wanted them to remain rationalist and Humanist, appreciating traditional archetypes for their psychological and artistic value. The litany she proposed for each meeting of such groups was “Who is our Goddess? Behold, she is ourselves.”

Behold that old-time Comtean Humanist religion in all its glory: collective humanity as the object of worship. It didn’t get far for Comte, and it didn’t get much farther for Walker, because normally human spirituality does not accept collective humanity as an object of worship. But it felt good at the time.

It also gave women an important guideline for any efforts to reclaim women’s status, in any religion. All viable religious groups, most definitely including the Christian Church, must rigorously purge out real abuses. A little heresy here and there may do no harm, but it probably took only a few actual human sacrifices to “goddesses” to get all goddess imagery, all religious women, all women teachers, even all women as citizens with the right to own property, smeared with the ugly reputation of “that woman Jezebel.” What Walker may seem, in the Encyclopedia, to be suggesting that women would want to reclaim, is exactly what she taught, in Women’s Rituals, that they should reject; what she is documenting, in the Encyclopedia, that women were blamed for and suspected of.

Fortunately, in our culture at least, for women religious scholars to resist the temptation of ritual cannibalism should be easy.

If you don't think reading this book will tempt you to practice ritual cannibalism, and want to buy it as A Fair Trade Book to show respect to Barbara Walker, you can buy a used copy here for $15 per book plus $5 per package plus $1 per online payment. Fat though it is, the original paperback edition was not oversized, so one or two more books with similar-sized pages will fit into the same package; I'm not sure whether The Woman's Dictionary of Symbols and Sacred Objects  would fit in along with The Crone or The Book of Sacred Stones (surely not all three), but if you want a complete collection I'll try. We'll send $2 to Walker or a charity of her choice for each copy of her Encyclopedia, and a corresponding payment for each of her other books you order through this web site.

would fit in along with The Crone or The Book of Sacred Stones (surely not all three), but if you want a complete collection I'll try. We'll send $2 to Walker or a charity of her choice for each copy of her Encyclopedia, and a corresponding payment for each of her other books you order through this web site.

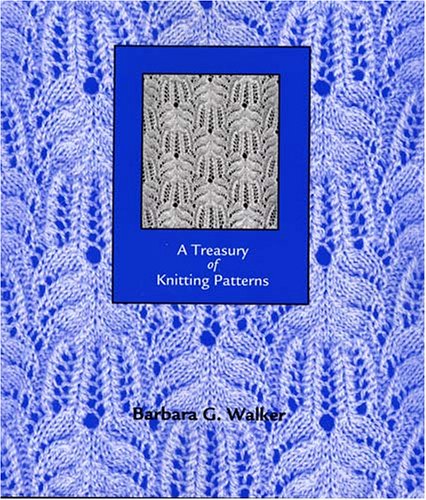

This post is long enough, but since it's obviously not about my favorite of Walker's books, let's add photo links for those of her books I wholeheartedly recommend to everybody...These are oversized, and thick--about 9x12x1" each--so the set of four fits nicely into two $5 packages. Buy them as new books from Walker's friend's daughter (now a Crone in her own right), who had them reprinted for sale as a set, if you can scrape up the $30 each; or buy used copies as Fair Trade Books from this web site if you don't mind getting the older, unmatched editions.

No comments:

Post a Comment