This week's butterfly, Byasa polla, has been through the usual rounds of name changes. As a Swallowtail it was first classified in the genus Papilio. As Papilio became crowded and naturalists wanted to divide it, this species was classified as a Tros and as an Atrophaneura before being placed, as it now usually is, in the genus Byasa.

Photo from Kedarbhide. It looks similar to one in the portfolio of Monsoon Jyoti Gogoi. MJG's photos are formatted to resist fair-use copying and the difference from Kedarbhide's may have been produced by some copying method more elaborate than CTRL-C, CTRL-V.

Byasa was named from the human family name Byas, but why polla? The Spanish word polla, pronounced Po-yah, properly means a pullet, a young hen not yet laying eggs. In urban slang it has at least three other meanings, two of which are extremely rude. This word has nothing to do with butterflies.

The butterfly species name is pronounced Po-lah or Poll-ah, and comes from Latin, not Spanish. In Latin it was a word, a variant form of paula, meaning small, and it was used as a personal name. At least six well-known Roman ladies were called Polla. A town in Italy is still called that today. All of them were known for belonging to rich families. None of them is remembered primarily for her funeral but a Google search for mortis Pollae brings up references to the cost of the funeral of the Emperor Vespasian's mother. In the eighteenth and into the nineteenth century, all the red-bodied and black-winged swallowtails were named after characters in literature who were associated with funerals.

If butterflies had to worry about what their names suggested to their official enemies in primary school, another Atrophaneura would have even more to complain about than this one. But we are not absolutely required to use its Latin name. It has an old traditional English name, De Niceville's Windmill, which commemorates Charles Lionel de Niceville, a butterfly enthusiast who worked at a museum in Calcutta. This name is French and should properly be written with an accent mark to remind people that the place in France was nee-seh-ville, not our English word "nice"-ville. During his short life (1852-1901), Lionel de Niceville wrote a three-volume study of Indian butterflies. He gave this species its Latin name.

The butterfly was a new discovery in De Niceville's time because it seems always to have been rare. It's another Asian species that likes fairly high altitudes in southerly latitudes. Paul De Gasse said it was found at elevations between 1200 and 2400 meters. Water has to be brought to a higher temperature to boil at altitudes below 1200 meters; 1200 meters is the point at which cooks start altering recipes. De Niceville's Windmill is found across Asia, from India to China, wherever the environment suits it; that's not a lot of places.

When an animal is naturally that rare, it's hard to estimate the extent to which it's endangered by human activity, and sources differ on the conservation status of De Niceville's Windmills. Vulnerable, threatened, or of least concern?

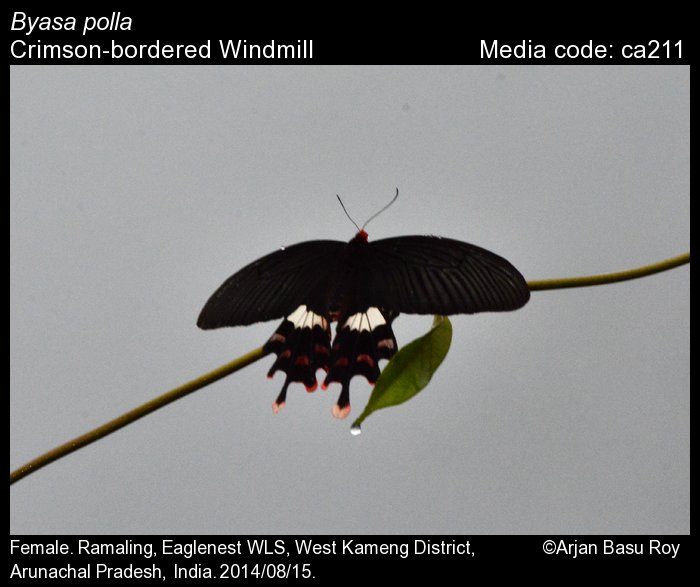

They are large, with wingspans from five to seven inches. The wings have that long, narrow "windmill" shape, with single "tails" on the hind wings. The tails have red tips. Males and females look pretty much alike. They have typical Atrophaneura fore wings, black along the veins, sometimes fading to brown or gray in between. Each hind wing has a white patch in the middle and smaller red spots around the edges. Females have bigger white patches than males, and males have a substantial "scent fold" of unscaled skin on the inside edge of each hind wing. The folds start out white and have been described as "woolly," but can fade to yellowish or brownish, as the white and red spots do, The outer edges of the hind wings are deeply scalloped and can look almost as if the butterfly had three tails on each hind wing.

They fly in spring and summer. Like the other big Atrophaneuras they are powerful fliers, sometimes seen flitting above the treetops in a forest.

They may also be found resting beside paths through the woods or sipping water from wet sand, as shown. This is a mixed group. Windmills and another species of swallowtails:

They seem to be strong; some photos of what have been accepted as Crimson-Bordered Windmills suggest that courtship behavior involves couples carrying each other about, high in the air.

Caterpillars are believed to eat Aristolochia. There seems to be only one generation per year.

This species can hybridize with Atrophaneura latreillei and has sometimes been classified as a subspecies of latreillei for that reason. Hybidization is sometimes listed among the threats to species survival. Hybridization, even to the extent of loss of distinctive genetic features, is not extinction--the distinctive DNA still exists and the distinctive genotype may reappear. Forest destruction is a real threat since it endangers all of the forest creatures together.

De Niceville's Windmill is legally protected, for what that's worth, from the sort of "collectors" who still think of a butterfly collection as a box of faded carcasses. The only way to make this protection meaningful is to stop buying dead butterflies, or parts of them, altogether. Anyone who observes butterflies is likely to find dead bodies, but we don't want to encourage killing rare butterflies before their time. Desperate students need to know that the way we collect butterflies now is in the more hygienic form of photographs, and there's no limit to the number of unique photographs a student might be able to snap and sell to collectors if the butterflies survive to be photographed another day.

Nevertheless, there are still web sites that offer carcasses of this species for sale. Those who buy dead butterflies need to know that, although the seller may have come by them honestly, the existence of a profitable trade in dead bodies is an ongoing threat to rare butterfly species. Butterflies' wings, like birds' worn feathers, are souvenirs the animals give to naturalists but these gifts should not be dishonored by selling them.

No comments:

Post a Comment