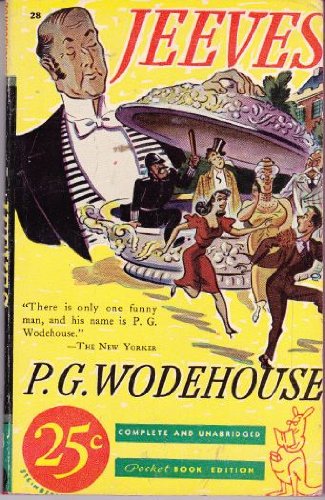

Title: Jeeves

(Interestingly, Amazon reports that although several people claim to have some version of this edition, some date-stamped 1943, what some of them are actually selling is a reprint of the text scanned into a computer. What I physically have is a pocket-size paperback book printed in 1939. A computer printout might offer larger, clearer type; I'd have no problem with it but I do understand how it might disappoint someone looking for the original vintage book.)

Author: P.G. Wodehouse

Author: P.G. Wodehouse

Date: 1923 (U.K.), 1939 (U.S.)

Publisher: Doran (U.K.), Pocket Books (U.S.)

ISBN: none

Length: 244 pages

Quote: “Jeeves...always floats in with the cup exactly two minutes after I come to life.”

Up to 1950, before telephones took over, living alone was almost unthinkable. Bachelors normally lived with parents or siblings; anyone with a steady income hired a “companion,” and anyone without an income could make “companionship” a job.

These relationships often went wrong. Ancestor-snobbery, the idea of a servant class who couldn’t possibly be fit to inherit property, had its base in the need to keep hired companions from murdering their employers. Though the whole hierarchy of hired companions, valets, tutors, nurses, butlers, housekeeper, ladies’ maids, and others, were at the top of the servant class, often well educated and (as servants went) well paid, they could still be “ruined” by a single false accusation.

But sometimes the relationships went right. Bertie Wooster, the rich, charming, witty, immature twenty-something “gentleman,” and Jeeves, the quiet, discreet, unctuously polite, older and wiser “gentleman’s gentleman,” are a comedic parody of the best-case scenario where the employer and employee become each other’s best friends.

Jeeves and Bertie use very formal manners to balance the excessive intimacy built into Jeeves’ job. Jeeves calls Bertie “sir” and Bertie, who naively narrates all the social blunders from which Jeeves tactfully rescues him, doesn’t seem to know whether Jeeves has a first name. They know each other’s secrets and always act in each other’s best interests. In real life they would probably have disagreed about Jeeves’ wages and social life too, but in the stories they always disagree only about fashion; Jeeves always cooperates with hardly more than a reproachful look, and always gets his way—meaning he gets Bertie to discard a tacky-looking fad item—in the end.

If Jeeves had been real, everyone would have wanted to know him, even after his natural life expectancy was over. Eighty years after his “birth” as a mature man in this novel, one of the first reliable search engines was called “Ask Jeeves.”

And this is where it starts. Jeeves begins with an episode that was also published as an independent “short” story (although it’s not very short), in which Jeeves not only spots the jewel thieves at the hotel but recovers the stolen jewels, and continues through several similar adventures until Bingo gets married. I read most of the other Jeeves, Blandings, and Psmith stories before I found this one. Knowing with whom Bingo was going to live happily ever after did not spoil the comedy of Bertie’s reluctant participation in Bingo’s love life for me.

That would be enough to say about this novel if I hadn’t found reason to disagree with the introduction to the reprint I have, on two points. Few people have read all of Wodehouse’s books—there were 97. I’ve read more than half of them, and I believe they contain evidence that Wodehouse became a target for political persecution because his first great comic character (based on a real person) made himself memorable by a political joke. I’m positive they contain evidence that Wodehouse was able to write clever, funny, lovable female characters who might have been played by Lucille Ball.

Wodehouse wrote several stories that grew into series of books. The one that launched his career was Mike and Psmith

From time to time Wodehouse tried working a different comedic vein. There was a series of short stories told in a club restaurant where tellers and listeners are identified by their orders as “Eggs,” “Beans,” “Crumpets,” etc. There was a working-class character, Mr. Mulliner. Wodehouse wrote several stories about golf. He was also attracted to the American crime fiction genre; he wrote several comic crime parodies. The crimes mostly involved stealing paintings and jewelry, the criminals were sympathetic goofs, and although in theory Wodehouse’s criminals spoke U.S. criminal jargon with a few fashionable British slang words they’d learned from movies, while his British aristocrats spoke upper-crust British English with a few fashionable bits of criminal jargon they’d learned from movies, in practice they all sounded more like Wodehouse than like other members of either group. In any case the golf, crime, restaurant, and Mulliner stories sold, but never so well as the adventures of the British elite group that included Psmith, Bertie, and Blandings. Wodehouse kept going back, by popular demand, to that improbably extended, improbably sunny, summery prewar England where the biggest problems on people’s minds were whether Bertie ought to wear purple socks and which of the Earl’s nieces and nephews had misplaced which Blandings family treasure on purpose to manipulate which of his siblings into agreeing to what.

By and large Wodehouse’s characters paid less attention to politics as their fictional world faded further into the nostalgic past, every year. Jeeves and Blandings stories don’t mention years, but the slang and fashions and other details suggest that, just as it’s always summer for these characters, the year is probably in the 1920s, surely no later than 1940. Hostility about Psmith’s summary of socialism, however, died hard. Wodehouse was no fan of Mussolini—he made fun of an unsympathetic character who did admire Mussolini in one of his novels—but he got stuck in Italy while Mussolini remained in power, and was forced to state on radio broadcasts that, though held prisoner, he was being treated well. There was a war on. Wodehouse was banished from Britain as a traitor, falsely accused of being the person who'd broadcast really anti-British propaganda as "Lord Haw-Haw," and forced to immigrate to the United States, which his fans tried not to make too much of a hardship for him. He stayed in the U.S. after clearing his name and died old, rich, and famous, but always scorned by some people because he hadn’t jumped on the socialist bandwagon.

Later a complaint arose that he didn’t like women characters. This complaint was based on selective reading of his best-selling novels only. There’s no question that Wodehouse, having gone to all-male schools and all-male clubs, made fun of those male-bonding sites more effectively than he made fun of happy families. Bertie’s pal Bingo Little, the commitment-phobic social butterfly in Jeeves, reappears as a comically clueless but happily married minor character in both Jeeves and Blandings novels. Part of Bertie’s comic ineptitude is his fear of women. Bertie is, for all practical purposes, married to Jeeves. Wodehouse used several versions of a story in which some other young man, less afraid of women generally but still shy about approaching the one he wants to marry, heeds a bit of bad advice found in pop culture of the period: “You must take her in your arms and say, ‘My mate!’” Despite this handicap all the more competent Wodehouse heroes married.

There are even a few Wodehouse heroines. Wodehouse seems to have liked the name Sally; he gave it to at least three characters who combined Jeeves’ presence of mind, Psmith’s cheekiness, and whatever style of prettiness was in fashion that year. The Sally stories made me laugh too. One Sally became the main character in a book

Wodehouse was more justly criticized for writing, or rewriting, frivolous unoriginal stories that aimed for hilarity at the expense of Literary Merit. There's no real suspense about a Wodehouse story; you know nothing very bad is going to happen to anybody, some characters are always going to be incompetent, others are always going to have all the answers, people who are especially tiresome are going to be embarrassed, everyone will laugh and make up at the end, and three-quarters of the plot in one story may be the same as three-quarters of the plot in another story. You don't read to find out what happened, but strictly to laugh. Writing this way can be defended as a separate art form but Wodehouse didn't write, and can't be read, in the way Shakespeare, Mark Twain, or even Dave Barry wrote and can be read.

Wodehouse’s “genius” contemporary, Charles Williams, whose weirdly mystical novels show a repressed sense of humor, had a character explain uncontrollable giggling with “It’s Jeeves...it comes in a book.” Possibly Williams envied Wodehouse’s gift of literary clowning; or perhaps he wanted to avoid a pun that seems obvious to anyone who majored in English Literature. Medieval English writers did not make a clear distinction between wood, meaning wood, and wode, meaning demented. The character’s giggling when strange and alarming things are going on raises suspicions...No fear, Gentle Readers. Laughing out loud physically relieves pain and the long-term effects of stress, and if you Choose Laughter to prevent becoming wode in times of stress or pain, this long-gone author can help.

To buy Jeeves online, send $10 per bound paperback book (with "25 cents" on the cover, yes) or $5 per samizdat printout, plus $5 per package and $1 per online payment, to the appropriate address as explained on the Payment Information Page. At least seven and probably eleven books of this size will fit into one $5 package, so feel free to browse for additional books to fill the box...if you choose books by living authors, we send them money to encourage them.

No comments:

Post a Comment