Thursday, August 15, 2024

Book Review for 8.7.24: Code of the West

Thursday, May 25, 2023

Book Review: Night and Day

Title: Night and Day

Author: Virginia Woolf

Date: 1919, 1971

Publisher: Penguin

ISBN: none

Length: 471 pages

Quote: “It suddenly came into Katharine’s mind that if some one opened the door at this moment he would think that they were enjoying themselves.”

Katharine is one of six young single adults in her neighborhood. If they were alive today, this little group would probably be a polyamorous community; they’re all young and hormonal enough to enjoy sex with practically anything, or anyone, and any of them could obviously enjoy a night with any other of them—at least, in a heterosexual pairing. They’re so hormonal, in fact, that they don’t even care that at least four of them are cousins to each other. This detail puts me off the whole pack of them, but Virginia Woolf managed to write almost 500 pages about the difficulties these incestuous Brits have in restricting themselves to one formal courtship, leading to one marriage, at a time. What a scandal it is that Katharine and William, who announce their engagement first and break it off first, actually remain friends and help each other marry the people they really want to marry.

Pet names aren’t used in this crowd. The girls are Katharine, Cassandra, and Mary. The guys are William, Henry, and Ralph. Katharine’s and William’s engagement was favored by their elders at least partly because they stand to inherit more money than Henry and Cassandra, and much more money than Mary and Ralph.

I find this tasteful, yet hormone-driven, study of youth very tiresome. I tried to read the whole novel in the 1990s, gave it up, and have only just finished it. The book qualifies as a study of why modern-style dating displaced traditional-style courtship in the twentieth century, why the rules of nineteenth-century-traditional courtship served our six characters so poorly. As such, it subjects readers to levels of impatience almost comparable with those the characters suffer…so caveat lector!

If you like long-drawn-out novels of manners, if you’ve always wished Jane Austen’s novels didn't try to be funny but just went on twice as long, if you're into incest and appreciate that in real life Virginia Woolf knew something about taboo relationships even closer than with cousins, then Night and Day might be your cup of tea. If you’re making a study of Virginia Woolf, you’ll need to refer to this novel. For readers in these two categories Night and Day is recommended.

Woolf is sometimes considered an important writer. I'm not sure why. She wasn't the first representative of any group; Pearl S. Buck, Rose Wilder Lane, Dorothy Sayers, Dorothy Parker, Marianne Moore, Edna St Vincent Millay, Elinor Wylie, even Mary Roberts Rinehart were writing better books, and the subcategory "suicidal women writers" was much better represented by Sylvia Plath. Call me heretical but I suspect Woolf's place in the twentieth century literary canon, such as it was, was created for her by grieving relatives in the literary community. Now they're all dead and gone, and Woolf's fiction has my permission to go and lie down among them.

Wednesday, February 12, 2020

Book Review: Hiding Ezra and Wayland

Underwhelmed, to say the least, by typing in mini-reviews of these two novels-from-family-history, hitting "Post," and having the book's home page pop back onto the screen with a smarmy little message saying "Priscilla King, write a review of [the book I just did]!"--I don't like web sites that bark orders at readers, in any case...I'm going back to my own blog. Which Google, of course, will try to hide from people, and Goodsearch will try so hard to hide that it'll even redirect readers back to cached copies of the posts for which Blogjob paid. Goodheavens, the corporate would-be rulers of the world cried, we mustn't let people discover a blog that blows the whistle on sneaky corporate censorship on the Internet!

If the Internet doesn't pull a U-turn and require human review before even the ugliest porn images and hatespews can be censored, how long do you think it can last? Two years? Three? It's been fun, and I look forward to getting paid again for my special talent for creating decent-looking documents on manual typewriters...

Here, while it lasts, are full-length reviews of two short paperback novels. They can be read independently; they're best read together.

Author: Rita Sims Quillen

Title: Hiding Ezra

Amazon details:

- Paperback: 220 pages

- Publisher: Little Creek Books (February 18, 2014)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 1939289351

And the sequel: Wayland

Amazon details:

- Paperback: 160 pages

- Publisher: Iris Press (September 16, 2019)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 1604542543

Rita Sims Quillen is best known as a poet. No worries for those who don't like poetry; these stories are not told in the sort of lush prose that tends to be described as "poetic." Landscape descriptions like "She also loved to go to a cool, shady bend in the little branch [creek] below the church where the trees created a canopy like walls" are as "poetic" as it gets. These novels get full marks for clear, straightforward prose that's not wordy, sentimental, or difficult to read. In fact one reviewer has quoted the first sentence of Hiding Ezra as an example of a good opening line for a novel.

They read like family history. Hiding Ezra is in fact based on family history--an old journal kept by a soldier who deserted from the Army in order to help his last few friends and relative survive a set of epidemic diseases that swept our part of the world in the 1910s and 1920s. Wayland might easily be based on another old journal.

Hiding Ezra is about the oddly enjoyable summer Ezra Teague spends hiding in a cave, leaving game near the homes of people who leave bread and ammunition near the cave. It's also about his grieving sister Eva, his faithful sweetheart Alma, and all the other friends and relatives they lose to the epidemics. It's also about Lieutenant Nettles, a nettlesome outsider from Big Stone Gap who connects with his inner decent human being after exposure to the grieving and loving people of Wayland, Gate City, and Fort Blackmore.

Wayland was the real name of one of the little rural settlements outside Gate City up to the 1940s, when it changed its name to Midway. Gate City had changed its name a bit earlier--in the nineteenth century it was called Estillville. Moccasin Gap, on the other side of the gap in the mountains formed by the Big Moccasin Creek, also changed its name, in the 1950s, to Weber City--spelled Weber, as in German, but pronounced Webber, as in English--after a radio comedy about a new subdivision: "The characters were having so much fun with their Weber City, we thought we'd have one too." In these novels place names are used as they were at the time.

When I read this novel, I enjoyed its dramatic climax, but wondered why the denouement was so long and so sad. A more tactful reviewer posted online that she wanted the story to be even longer, to resolve the new issues the denouement raises for the characters. Readers be warned. The last few chapters of Hiding Ezra are the trailer for Wayland.

In between reading the two stories, I cried. I won't spoil the denouement, I think, by explaining that I don't cry about fictional characters. No, but once when the words "rock hall" triggered a memory an 85-year-old great-uncle said, "My sister and sister-in-law used to take bread to the fellows that hid in the rock house." (Actually he used their given names, and one of them was still alive to confirm his claim.) My mother wondered if he was remembering the story she'd heard about my great-grandfather leading a party of soldiers to the nearby "rock house," a cave big enough for people to camp in. No, he said, this was in his lifetime...but he was weak and never had much to say at one time, and never mentioned the cave story again.

In my family the young spoke more frankly to the old, and asked more questions, than in some neighboring families. Still, I never asked for more details about feeding the deserters in 1918. I knew the cave was real; my brother and I had been shown how to find it on condition that we not try to get inside it. I knew Great-Aunt belonged to a pacifist church, and her sons were conscientious objectors, but her husband, Grandfather's brother, was exempt from military service because he was a minister. The great-uncle who first mentioned the story had one of those given names that commemorate a family friend's given and family names: Otto Quillen.That's all I can add to the facts behind Hiding Ezra.

What made me cry was that this story made me realize how lucky the elders were. My grandfather and eight of his younger siblings lived to ages between 75 and 99. Many of their generation did not. Physically and emotionally my elders survived by keeping a healthy distance between themselves and any friends they'd had as children...and even in the 1960s I still grew up hearing "Don't get closer to town children than you can help, don't go into town unless it's necessary, don't EVER go into a swimming pool, don't go to other people's houses and if you do don't eat or take off your shoes..." Two generations later, my extended family are still known as a stand-offish bunch. Possibly the elders' losses of friends to the epidemics had something to do with that. I've heard a lot of rot about possible kinds of "hurt" might have caused our family subculture to be so clannish, but this insight rang true. And it did hurt, briefly, wondering how many school friends my elders had buried...Grandfather was one of fifteen children, eight of whom lived to ages between 75 and 99. In another family of fourteen, six children born before 1940 were still alive in 1970.

Anyway: Ezra Teague survives his adventure, but the epidemic diseases and early deaths aren't over. In Wayland Ezra has left his daughter for his sister to raise. Eva has indeed married Lieutenant Nettles, who is now a nice guy but still insecure enough to be impressed by a stranger's show of respect. That insecurity places the Nettles family at risk when the lieutenant offers a job to a "hobo" who calls himself Buddy Newman. Newman's real name is Deel, as in Scottish "de'il," and his character is a study in Human Evil. He wants to set people against each other, ruin the reputation of a pious but sex-starved old lady, and do even worse things to little Katie Teague.

The suspense of the story is finding out whether Newman's schemes will be foiled, and how, and by which of the decent local folk. There is an interesting and thoroughly local delineation of the relative vileness of Newman, an otherwise likable hobo who has an icky relationship with a teenaged boy, a rude drunk, and a murderer. Newman is a bigot, a pedophile, and also a murderer, but his evil runs deeper than that. (The narration of his evil won't embarrass readers in front of their children but the single telling details, when they emerge, may upset children.)

Did an ancestor really keep a diary that narrated such events? At least they're not the local pedophile story I always heard: it would have been fifteen or twenty years later when the man I heard described as "an escaped mental patient" did some physical damage to a local primary school girl. And I was glad. I did not want that girl, who survived but never married, to have been the real model for Katie. (Katie is characterized as pretty much the perfect niece in Eva's diary, but aunts know to allow for another aunt's auntly perspective. I think each of The Nephews is pretty much a perfect child, too, in his or her own way.)

Once again, after the main plot has resolved itself, the last two chapters go on. I didn't cry while reading Wayland but I found the denouement somewhat sad. Others may like it but I think they'll agree that, once again, the last chapters of Wayland are a trailer for another story.

I gave both books five stars on Goodreads for Keeping It Real. These are not just another stereotype of "Appalachia," the whole mountain range, from Georgia to Nova Scotia and possibly also Britain, confused with old pictures of the coal-mining town. Anything looks grim in a black-and-white photograph. In these books we see Scott County much closer to the way it must have been, between 1917 and 1930, to have become what it's been in Quillen's and my lifetime. I'm delighted.

Thursday, June 14, 2018

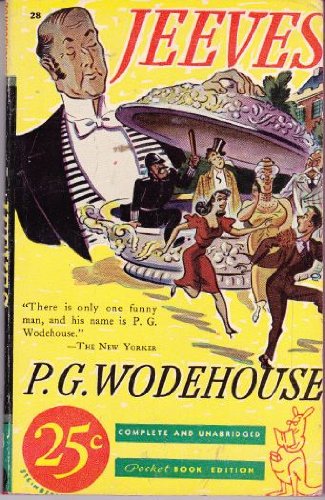

Book Review: Jeeves

Author: P.G. Wodehouse

Date: 1923 (U.K.), 1939 (U.S.)

Publisher: Doran (U.K.), Pocket Books (U.S.)

ISBN: none

Length: 244 pages

Quote: “Jeeves...always floats in with the cup exactly two minutes after I come to life.”

Up to 1950, before telephones took over, living alone was almost unthinkable. Bachelors normally lived with parents or siblings; anyone with a steady income hired a “companion,” and anyone without an income could make “companionship” a job.

These relationships often went wrong. Ancestor-snobbery, the idea of a servant class who couldn’t possibly be fit to inherit property, had its base in the need to keep hired companions from murdering their employers. Though the whole hierarchy of hired companions, valets, tutors, nurses, butlers, housekeeper, ladies’ maids, and others, were at the top of the servant class, often well educated and (as servants went) well paid, they could still be “ruined” by a single false accusation.

But sometimes the relationships went right. Bertie Wooster, the rich, charming, witty, immature twenty-something “gentleman,” and Jeeves, the quiet, discreet, unctuously polite, older and wiser “gentleman’s gentleman,” are a comedic parody of the best-case scenario where the employer and employee become each other’s best friends.

Jeeves and Bertie use very formal manners to balance the excessive intimacy built into Jeeves’ job. Jeeves calls Bertie “sir” and Bertie, who naively narrates all the social blunders from which Jeeves tactfully rescues him, doesn’t seem to know whether Jeeves has a first name. They know each other’s secrets and always act in each other’s best interests. In real life they would probably have disagreed about Jeeves’ wages and social life too, but in the stories they always disagree only about fashion; Jeeves always cooperates with hardly more than a reproachful look, and always gets his way—meaning he gets Bertie to discard a tacky-looking fad item—in the end.

If Jeeves had been real, everyone would have wanted to know him, even after his natural life expectancy was over. Eighty years after his “birth” as a mature man in this novel, one of the first reliable search engines was called “Ask Jeeves.”

And this is where it starts. Jeeves begins with an episode that was also published as an independent “short” story (although it’s not very short), in which Jeeves not only spots the jewel thieves at the hotel but recovers the stolen jewels, and continues through several similar adventures until Bingo gets married. I read most of the other Jeeves, Blandings, and Psmith stories before I found this one. Knowing with whom Bingo was going to live happily ever after did not spoil the comedy of Bertie’s reluctant participation in Bingo’s love life for me.

That would be enough to say about this novel if I hadn’t found reason to disagree with the introduction to the reprint I have, on two points. Few people have read all of Wodehouse’s books—there were 97. I’ve read more than half of them, and I believe they contain evidence that Wodehouse became a target for political persecution because his first great comic character (based on a real person) made himself memorable by a political joke. I’m positive they contain evidence that Wodehouse was able to write clever, funny, lovable female characters who might have been played by Lucille Ball.

Wodehouse wrote several stories that grew into series of books. The one that launched his career was Mike and Psmith

By and large Wodehouse’s characters paid less attention to politics as their fictional world faded further into the nostalgic past, every year. Jeeves and Blandings stories don’t mention years, but the slang and fashions and other details suggest that, just as it’s always summer for these characters, the year is probably in the 1920s, surely no later than 1940. Hostility about Psmith’s summary of socialism, however, died hard. Wodehouse was no fan of Mussolini—he made fun of an unsympathetic character who did admire Mussolini in one of his novels—but he got stuck in Italy while Mussolini remained in power, and was forced to state on radio broadcasts that, though held prisoner, he was being treated well. There was a war on. Wodehouse was banished from Britain as a traitor, falsely accused of being the person who'd broadcast really anti-British propaganda as "Lord Haw-Haw," and forced to immigrate to the United States, which his fans tried not to make too much of a hardship for him. He stayed in the U.S. after clearing his name and died old, rich, and famous, but always scorned by some people because he hadn’t jumped on the socialist bandwagon.

Later a complaint arose that he didn’t like women characters. This complaint was based on selective reading of his best-selling novels only. There’s no question that Wodehouse, having gone to all-male schools and all-male clubs, made fun of those male-bonding sites more effectively than he made fun of happy families. Bertie’s pal Bingo Little, the commitment-phobic social butterfly in Jeeves, reappears as a comically clueless but happily married minor character in both Jeeves and Blandings novels. Part of Bertie’s comic ineptitude is his fear of women. Bertie is, for all practical purposes, married to Jeeves. Wodehouse used several versions of a story in which some other young man, less afraid of women generally but still shy about approaching the one he wants to marry, heeds a bit of bad advice found in pop culture of the period: “You must take her in your arms and say, ‘My mate!’” Despite this handicap all the more competent Wodehouse heroes married.

There are even a few Wodehouse heroines. Wodehouse seems to have liked the name Sally; he gave it to at least three characters who combined Jeeves’ presence of mind, Psmith’s cheekiness, and whatever style of prettiness was in fashion that year. The Sally stories made me laugh too. One Sally became the main character in a book

Wodehouse was more justly criticized for writing, or rewriting, frivolous unoriginal stories that aimed for hilarity at the expense of Literary Merit. There's no real suspense about a Wodehouse story; you know nothing very bad is going to happen to anybody, some characters are always going to be incompetent, others are always going to have all the answers, people who are especially tiresome are going to be embarrassed, everyone will laugh and make up at the end, and three-quarters of the plot in one story may be the same as three-quarters of the plot in another story. You don't read to find out what happened, but strictly to laugh. Writing this way can be defended as a separate art form but Wodehouse didn't write, and can't be read, in the way Shakespeare, Mark Twain, or even Dave Barry wrote and can be read.

Wodehouse’s “genius” contemporary, Charles Williams, whose weirdly mystical novels show a repressed sense of humor, had a character explain uncontrollable giggling with “It’s Jeeves...it comes in a book.” Possibly Williams envied Wodehouse’s gift of literary clowning; or perhaps he wanted to avoid a pun that seems obvious to anyone who majored in English Literature. Medieval English writers did not make a clear distinction between wood, meaning wood, and wode, meaning demented. The character’s giggling when strange and alarming things are going on raises suspicions...No fear, Gentle Readers. Laughing out loud physically relieves pain and the long-term effects of stress, and if you Choose Laughter to prevent becoming wode in times of stress or pain, this long-gone author can help.

Thursday, April 5, 2018

Book Review: Emil and the Detectives

Friday, January 26, 2018

Book Review: Through Charley's Door

Author: Emily Kimbrough

Date: 1952

Publisher: Harper & Row

ISBN: none

Length: 273 pages

Quote: "To be economically independent is the only way I know for a woman to become mentally independent."

Emily Kimbrough's mother was saying that in 1923 as she encouraged young Emily to get a job, even though Emily was embarrassed by "the sentiments I knew were hers and hers alone." She might have been even more embarrassed when her mother "in private...expanded...that though I would be fed, housed, and clothed, whatever I wanted or needed above the bare necessities--and very bare, she inevitably stressed--would have to come of my own providing." And, of course, the most embarrassing part of all must have been that when Emily and her school friend, Cornelia Otis Skinner

Luckily, Emily Kimbrough's glib, easy writing style happened to be what the Marshall Field department store was looking for, and her ability to shoehorn poetry into advertising slogans even seemed fresh in 1923. So young Emily entered the store "through Charley's door," the most fashionable side of the store, and became a successful ad writer.

Although Through Charley's Door contains some social commentary and lots of amusing anecdotes, libraries classified it as a business study; Kimbrough was greatly impressed by the way her employer did business. Those familiar with the stories of stores that went national or international during this period (Sears Roebuck, Montgomery Ward, J.C. Penney, et al.) will notice a certain common thread in all these stories, as in the more recent Wal-Mart success story. Some hardworking entrepreneur with a fanatical dedication to customer service built a single store into a huge corporation. Later the entrepreneur retired or died, the company had grown too big to offer comparable dedication or service, and reminiscences of the store's early days seem bitterly ironic to anyone who's had to do business with the store as it has become...

Through Charley's Door still has good business advice to offer today's hardworking entrepreneurs, and may also interest those studying women's history. Both Emily Kimbrough and Cornelia Otis Skinner wrote several volumes of memoirs and observations, separately and together. Skinner was the source of the memorable one-line observations. Kimbrough's independent work lacks one-liners, but makes up for it in historical details and amusing anecdotes. Skinner was the city sophisticate; Kimbrough wrote as a wholesome Midwesterner who happened to have gone to college. Their collected work makes an interesting study in social history and in friendship between women who appreciated, and cultivated, very different styles.

As a story, Through Charley's Door could be classified as "chick lit": no life-and-death suspense, not even a romance, although the dedication page suggests romance offstage; suitable for reading in bed when you want to get up on time in the morning.

It's a collector's item, though. Unlikely to be reprinted, yet of interest to some book collectors, it's currently available from this web site for only $15 per book plus $5 per package plus $1 per online payment. Three more books of this size will fit into one $5 package, if that's any consolation to you, and you're free to let them be books by living authors who can at least be encouraged by the Fair Trade Books system...

Thursday, January 4, 2018

Book Review: Nods and Becks

Nods and Becks was popular in its day and has not reached collectors' prices as outrageous as might have been expected; lots of copies are still floating around. Send $5 per book, $5 per package, and $1 per online payment, to order this book as part of a package to which you can add three more books of similar size, including some by living authors whom we can encourage by sending percentages of the payment.

Tuesday, September 5, 2017

Book Review: More than Wife

Date: 1927

Publisher: Grosset & Dunlap

ISBN: none

Length: 310 pages

Quote: “I know that you had what seemed to me an irrational terror of being made into an adjunct of your husband, knowing yourself as forceful and as talented.”

Yes. That’s the way Widdemer’s characters talk. But first a bit of historical rant, which is common knowledge for baby-boomers but may be new to the young:

Up into the early nineteenth century, although most people worked, few people commuted. Both men and women usually lived very near where they worked. During the nineteenth century a gender split, first visualized and publicized by the French Socialists, took place; more men began to commute to jobs “outside the home,” while women stayed with the childen all day. Not only schools and crop fields, but stores and offices, gradually began to be built more than a five-or-ten-minute walk from the workers’ homes. The mass marketing of automobiles allowed really exploitative employers to assign people to jobs in completely different cities from home.

As individuals began to adjust their lifestyles to all this commuting, bickering arose about who ought to do what. The French Socialists and Humanists embraced a strange new idea that women had a sacred duty to preserve the home in a pristine pre-industrial state. In order to do this, women needed not only to be protected from the sexual temptation of mingling with men in schools and workplaces, but also to be spared from the emotional burden of having any adult responsibilities at all. By remaining as ignorant and sheltered as children, women were supposed to sustain some sort of mystical emotional atmosphere that would revive the burdened spirit of the middle-class working man. In feudal France women had been denied the right to inherit titles and property; the Socialists and Humanists wanted to revive this system of sexist discrimination and make it stronger. To a surprising extent, these anti-Christians succeeded in spreading the strange gospel of modern sexism through Europe, Britain, and America.

Poor women were not expected to be full-time permanent “angels in the home.” Though denied education, property, and the vote, poor women (and children) were usually paid less than their men, but not necessarily assigned lighter tasks. Affluent women were, however, barred from “competing with men” for jobs anybody was likely to want.

By 1927 many Americans believed the easily refuted claim that the Bible teaches that women should not have jobs of their own outside the home.

In fact the Bible does mention that women were banned from the regular army—and were accepted, and admired, in most of the “career roles” that existed in ancient Israel. Proverbs 31 rather plainly says that the ideal wife is not the prettiest or the most charming (“Charm is deceitful and beauty is vain”) but the most enterprising. At first, when the family are young, “she seeks wool and flax, and works willingly with her hands,” to clothe the family first. When “all of her household are clothed in double garments,” “She delivers a garment to the merchant.” With the profits from that venture “She considers a field, and buys it...she plants a vineyard.” Solomon was considered a wise king, not because he was a great preacher or philosopher, but because he built up the wealth of Israel, and in the books associated with his name the ideal woman is wise in the same way.

Nevertheless, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries competition for good jobs was real and earnest. Many universities simply refused to admit female students; many employers simply refused to hire women. When women persisted in becoming competent doctors, engineers, etc., they were solemly told that they would now be regarded as freaks, outcasts, heartless greedheads who were competing against their own husbands. And who’d hire them? Women architects? Whoever heard of a woman architect?

This is the context in which More than Wife, which I’m encouraged to hope many young readers will find bizarre, was written. Silvia, we are told, loves being an architect, and is a good one, though we don’t see her actually being one in this story. She marries Richard. Does she have to give up her work to be married? At this period it was normal for marriage to be synonymous with retirement for clerks, waitresses, and schoolteachers, but an architect could work partly at home...I’m sure Widdemer was inspired partly by newsreel coverage of Lillian Moller Gilbreth

What readers can like about More than Wife is that Silvia is not bullied into “choosing” to be a full-time mother and leaving that architect’s job open for some hypothetical veteran. Silvia and her family a “modern” and sophisticated and avant-garde enough to agree that a woman can be competent on a job even if she takes a few years off to have babies.

What I didn’t like about More than Wife is that Widdemer fails to convince me that Silvia is an architect. In The Fountainhead

Nevertheless, if (as the publisher put it) you’re in the mood for a clean, wholesome romance, More than Wife is one. If I can’t quite suspend disbelief that Silvia has a real talent and future as an architect, I can suspend disbelief that she and Richard were based on a real couple. More than Wife was probably never on anyone’s short list for Novel of the Year, but for train, waiting-room, or bedtime reading it’s adequate. (And, of course, for those who buy any "antique"-looking book as a decor item, it's excellent.)

(Does this post need some kind of photo link? Why not...Lillian Moller Gilbreth was not an architect, but her idea of "the efficiency kitchen" happened to overlap with Frank Lloyd Wright's. Here are two different books than the ones linked to their names, above.)

Thursday, August 17, 2017

Book Review: The Chinese Parrot

That's what I physically have. Amazon isn't showing copies available online, although you can get one from this web site for an appropriate collector's price. For readers not willing to pay collectors' prices, there's a reprint:

Author: Earl Derr Biggers

Date: 1926

Publisher: Grosset & Dunlap

ISBN: none

Length: 316 pages

Quote: “Detective-Sergeant Chan, of the Honolulu police...Charlie left us to join the police force, and he’s made a fine record there.”

Charlie Chan was one of several fictional characters that were created to express Anglo-American good will toward People Different From Us. Smart, tough, funny, he solved mysteries “with the patience of his race,” helping to break down the stereotypes that had been based in real hate and fear while building up the more benign kind based in mere ignorance. He was very popular in the early twentieth century. (By the time I came along, a cartoon spin-off series was popular on television; I never watched the show but had a “Chan Clan” cartoon lunchbox decorated with scenes showing Charlie Chan’s ten children.) Before the movies, there were the novels, at first rather cheaply produced hardcover novels...and this is where it starts. Although the hardcover binding is not in very stable condition, what I have is a first edition of The Chinese Parrot, printed in 1926.

It’s a classic detective story. Much more than that I can’t say without spoiling the suspense, but I will say that although the psychology is dubious and the police procedure is at best long out of date, it’s a fun read.

Part of the fun is in Biggers’ attention to words. Charlie Chan does not enjoy clowning—“shuffling,” playing the stupid laborer who knows only a little pidgin English, although he does that in some scenes; he’s proud of his English vocabulary. At a period when silly “Confucius Say” jokes were in fashion (“Confucius say: one who sits on tack is better off!”), Detective-Sergeant Chan always had a real proverb, some even translated from “Kong Fu-Tse” (older transliteration style throughout). At the same time his English remains the sort of English we expect to hear real educated foreigners speak, with each word recognizable, but not necessarily used in the same way a native speaker might use it. Most of the time audiences were laughing with Charlie Chan (or just trying to solve mysteries with him) but then again, once or twice in each story, they got to smile at him.

For vintage movie watchers, another nice touch about the book is that it’s not as sexist as you might have expected. Of course the young woman is kept on the sidelines and referred to as a “girl,” but then the young man is likewise called a “boy,” throughout. At least “girl” Paula isn’t stupid, weak, or helpless; she’s a distraction for “boy” Bob from his adventure with Charlie Chan, because she has her own job to do; she does need to be rescued, once, along with an older woman and an older man who—oh, read the book, but suffice it to say it’s not because Paula faints at the mention of danger.

For protective parents, an additional nice touch is the low level of violence (by grown-up detective story standards). Fictional detectives can almost never solve one murder case until the murderer commits a second murder, but in this book...solve it yourself...there aren’t as many murders as we at first suspect, and the only murder we “see onstage” is that of the parrot.