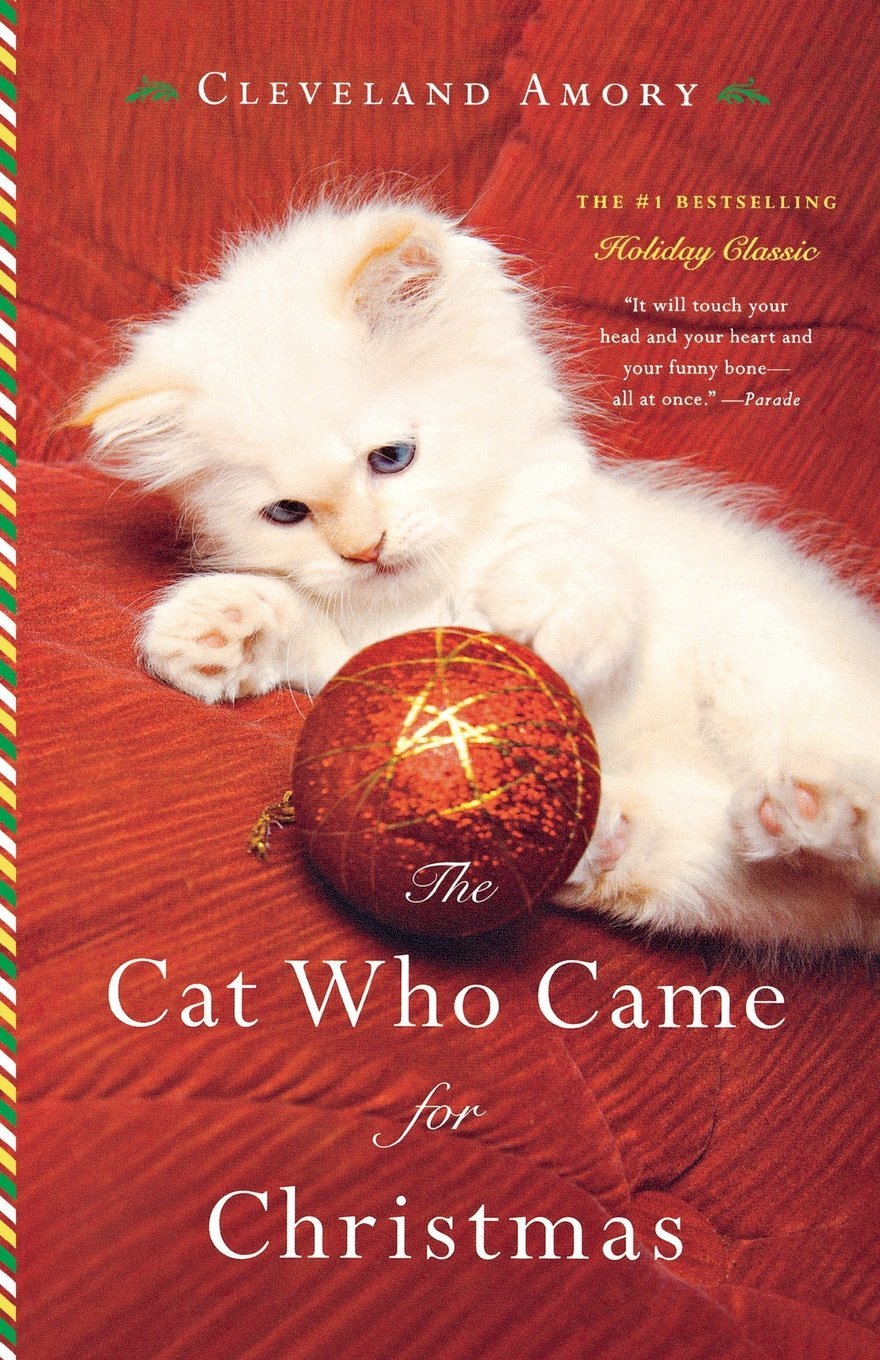

Title: The Cat Who Came for Christmas

Author: Cleveland Amory

Date: 1987

Publisher: Penguin

ISBN: 0-14-01-1342-8

Length: 240 pages

Illustrations: drawings by Edith

Allard

Quote: “To the biographee, the

best cat in the whole world—with the exception, of course, of yours.”

Cleveland Amory literally picked

up a cat in an alley. The cat had gone feral; one of Amory’s friends had been

trying to adopt him, without success, “for almost a month.” After biting and

scratching Amory a few times, and being fed inside Amory’s apartment anyway,

the cat decided to become a pet. When cleaned up he turned out to be white, so

Amory and his friends at the World Wildlife Fund named him Polar Bear. By staying

with Amory and the WWF home office, Polar Bear became a celebrity. He lived,

thrived, and grew old on all the attention.

As you read his biography, you

may begin to wonder which was the humorist, Polar Bear or Amory. From his other

books it’s apparent that Amory was. He wrote only one book that was

specifically meant to be funny more than to provide information. All of his

books are, nevertheless, likely to make readers laugh out loud.

His descriptions of what might

have been, to some people, an ordinary pet cat, are a case in point.

Do cats answer to names? Few cats

will consistently come running when their names are called (although some of

mine do). Many, not all, white cats

are born deaf. Studies done with elaborate sound equipment have determined that

some cats have names for their humans (a specific “meow” that companion animals

recognize the cat using to call the human’s attention and not theirs) and that

most humans don’t realize that they’ve been given names in cat “language.” Not

surprisingly, simpler studies have determined that most cats don’t seem to

realize that they’ve been given names in human language, either. The amazing

thing is that some cats do listen to humans and understand words.

Polar Bear, typical of the sort

of stray/feral cat who was once a badly treated pet (or considered himself

one), had learned to beware of any human who appeared to be calling. Some cats do unmistakably make

this a rule. Our pets do not always make a clear distinction between abuse and

veterinary care. I lived with one cat, Minnie, who had learned her name before she came

to associate being called with being taken to the vet. She’d forgiven me, up to

a point; she’d follow me around the house, soliciting petting and grooming, or

even ride on my shoulder; but she never completely trusted any human again, and

if she were sitting on my lap and heard me or anyone call her, she’d run under the porch.

Amory’s take on Polar Bear’s

response: “Cats,he was clearly saying, do not come when called…What about when

it was something they wanted—like dinner? He visibly sighed. ….The way we

worked it out was that I was never to say ‘Come’ or ‘Come here’ or anything

like that…However, I would be permitted more subtle indications…such as

directing an inquiry to the world at large…where he was.”

Amory apparently was willing to

make certain sacrifices to bond with his rescued feral cat. Many cat owners

have admitted doing all sorts of things that make other cat owners think, “Eww,

I would never…” Marge Piercy  admits having once bonded with a sick kitten by

licking it. Amory admits: “My cat was very fond of breakfast, and after he had

eaten his,he was very fond of eating mine too. In vain…I lectured him that I

had been brought up in a home where animals were not allowed in the dining

room…So…we compromised. I agreed to let him up on the table if no other guests

were present, and he in turn agreed not to eat anything at the same time I was

eating it…if the spoon was still in motion, it was still my turn; if it wasn’t,

it was his.”

admits having once bonded with a sick kitten by

licking it. Amory admits: “My cat was very fond of breakfast, and after he had

eaten his,he was very fond of eating mine too. In vain…I lectured him that I

had been brought up in a home where animals were not allowed in the dining

room…So…we compromised. I agreed to let him up on the table if no other guests

were present, and he in turn agreed not to eat anything at the same time I was

eating it…if the spoon was still in motion, it was still my turn; if it wasn’t,

it was his.”

Amory had read a great deal about

cats. If he chose to share not merely a dish but the actual spoon with a cat,

that was his lookout; anyway he died old. His reading had, however, been

somewhat selective. “The Bible…which refers to almost every other animal,

has practically no references to cats,” he observes. This is true but Amory

accepts a theory without reference to the historical evidence available.

Domestic cats evolved fairly recently, through highly selective breeding. In

some parts of Egypt semi-domesticated cats were worshipped, but they weren’t

kept as house pets. Biblical Hebrew has words for “lion” and “leopard” but not,

specifically, for smaller cats, probably because ancient Israelites weren't familiar with smaller cats.

Even in New Testament times, although Aramaic had developed a word for “pet dog” that

was different from the Hebrew word for “wild dogs,” it is instructive that only

the Syro-Phoenician woman uses it. (Latin had a word that was used for semi-tame cats and semi-tame weasels, which were kept for the same purpose, primarily as hunters and fighters rather than pets.) Ancient Israelites did keep pets. They recognized

that killing someone’s pet was very different from killing an animal raised for

meat. However, the animals ancient Israelites kept as pets were goats, sheep,

pigeons, and chickens—the individual animals with whom individuals humans

bonded, from the flocks of animals humans raised for food.

Amory had read several

explanations of how cats in history got their names: “All animals, I explained,

when they are domesticated and live with people, have names…Just the way, I

went on, people have names…My name, for example,I told him, is Cleveland. He

gave me a long look…It was clear he felt I should, and as quickly as possible,

seek professional help.”

Once the cat had been vetted and

named, his human sought the help of professional actors for a WWF anti-cruelty

campaign: “Polar Bear did at last get to meet a movie star, and it was

eminently fitting that, when he did, it turned out to be one of the greatest of

them all. It was Cary Grant.” Grant “had always been a dog man” until “Polar

Bear…jumped up in his lap.” “In his last years, Cary did have cats, and

although people were inclined to attribute this to…his wife Barbara…I always

thought Polar Bear deserved at least some of the credit.”

Amory had valid reasons for

keeping Polar Bear indoors: they were in New York City, they were minor

celebrities, and a dog had attacked Polar Bear when Amory got the cat to walk

on a leash. His opinions on confining cats, generally, are worth mentioning.

Amory didn’t try to claim that cats are actually a threat to birds (they are in Australia, New Zealand, and Hawaii, but in North America they're not), but that “his

neighbor…may enjoy his birds just as the cat owner enjoys his cat.” In other

words, the urban bird fancier may enjoy luring “his birds” to behave in

unnatural ways that endanger their lives. I find this argument specious. If

these people enjoyed birds half as much as I do, they’d enjoy building bird

houses and feeders that protect the birds not only from being chased by cats

but from having their food stolen by mice or squirrels.

The conclusion of The Cat Who Came for Christmas is that

“we have had so much fun together that…I hope…those of you who have never had

an animal will hie yourselves to the nearest shelter, and adopt one.” In 1987

animal shelters were still rescuing genuinely homeless and unwanted animals in

cities, being far from the current HSUS goal of rendering domestic animal

populations extinct. I doubt that Amory foresaw a day when adopting a shelter

pet was likely to mean enabling covertly for-profit shelters to cash in on

petnapping. Unfortunately, that is now the case.

Amory didn't live to see the day when "nice" city neighborhoods that had enacted laws ordering that all cats be kept indoors, to protect birds, would have allowed rats to reach the top of the food chain. I've seen that, and I now think that, far from recommending that cats be kept indoors, everybody should be posting this slogan everywhere:

GOT SEPTICEMIA? THANK A FREE-RANGE CAT!

Meanwhile, until we have strict laws

about removing shelter animals from the neighborhood in which they were found,

and about publishing photos of all animals brought to shelters together with

the people who brought them in, and generally ensuring prison time for

petnappers, together with laws limiting animal shelters to a maximum “adoption

fee” of ten dollars and forcing them to rely on donations to feed genuinely

homeless animals, what today’s readers are likely to “adopt” from animal

shelters are likely to be dogs and cats stolen from the yards of people who

live in a different state. A friend’s kitten or puppy is likely to be a better

pet for a first-time pet owner anyway.

(Should you adopt a senior cat or dog from a shelter? Shelters still legitimately acquire old animals from people who aren’t willing to play geriatric nurse to a cat or dog. If you can verify that the animal wasn’t stolen, elderly animals usually have medical issues but they have more stable personalities; they seem to develop fewer behavioral issues from the trauma of being in the shelter.)

Your experience as a pet owner is unlikely to resemble Amory’s. (For one thing, even if you schmooze with

movie stars in aid of a charitable organization that you’ve organized, it’s too

late to mingle with the ones Amory knew.) You and your pet can, however, have

fun together. If lucky, you can enjoy a dog’s or cat’s company as long as Amory

enjoyed Polar Bear’s, or longer. A dog or cat who lives more than ten years is

definitely an old animal, but if blessed with humans who are willing to nurse them through the infirmities of old age, some cats and dogs live fifteen or even twenty

years.

No comments:

Post a Comment