Although I started "gardening" at age six (along with everyone else in Mrs. Fats' first grade class, except a few people who were already bragging of having reached age seven) it would not have occurred to me to describe myself as a Master Gardener. Nor would I have ever expected to find myself correcting a Master Gardener's mistakes.

Nevertheless, no less a newspaper than the Kingsport Times-News allowed one of the Master Gardeners to disgrace perself, anonymously, as follows:

"Q. Master Gardeners, I have black and gold caterpillars with white dots crawling all over webs in my barberry bushes. Are they...pests? I have seen this before...but not to this extent so I have never given it much attention. They've all but decimated the bushes this year. You could actually hear the munching..."

"A. These beasts are tent caterpillars and they are a common pest in Tennessee every year. They form web-like tents around the junctions of tree branches where the eggs hatch and become voracious caterpillars that can completely defoliate young trees and shrubs. Fortunately, they only visit and eat once a year during August here in Tennessee."

Whew. Where do I begin?

With the observation that confusing any Master Gardener to this extent is the work of a true career professional in confusion. That is what caterpillars are. It is what they have to be if they want to live. Mostly, in their dim unconscious way, they do want to live; and so, in a variety of unconscious and involuntary ways, they are confusing. Their main focus is on confusing birds but they will happily confuse humans if they get a chance.

Tent caterpillars belong to the genus Malacosoma in the family Lasiocampidae. Though not so large as some of the Sphingids and Saturnids, they look large compared to the caterpillars the reader was describing. There are a few different species (how many depends on which authority we consult) but only M. americana, or americanum or americanus, again depending on whose book we're reading, is much of a nuisance in eastern Tennessee. Most tent caterpillars do build their tents around forks in the branches of tall fruit trees, where it's harder for enemies to reach them and easier for them to reach the juiciest new leaves. They do most of their munching, in Tennessee, in April. Arguably they become even more of a nuisance in May, when they stop eating and wander about underfoot. They are never observed in August.

What this reader was describing belong to the genus Hyphantria in the family Arctiidae. It used to be believed that there were two distinct species of these caterpillars, Spring and Fall Webworms; now it seems to be agreed that they're different color variations, possibly from distinct bloodlines but still basically the same animal, H. cunea, or Webworms. People are more likely to see green and yellow ones with little black dots in May or June, black or dark brown ones with yellow and white markings in August or September. At the Cat Sanctuary we generally see the green and yellow ones in July and August. They form much thinner tents around the ends of branches, enclosing the leaves, on low bushes. They don't often defoliate the host plant, but they can, especially in a bad-weather year like 2022.

Other species vary a bit but Malacosoma americana is a fascinating study in adaptation to its environment, and in what looks like warmhearted, loyal, loving behavior in a coldblooded animal with hardly anything in the way of brain. Despite these caterpillars' alarming behavior during their regularly recurring "plague years," they are part of eastern North America's natural environment and, overall, they do nobody any harm. North American trees are built to survive one complete defoliation, by late frosts or voracious caterpillars, with little effect even on the fruit crop.

The population of Malacosoma americana follows a ten- to twelve-year cycle. Having few natural predators, because their preferred diet of leaves from trees in the genus Prunus fills their bodies with so much cyanide their skins even turn bluish, the insects multiply every year until they become overcrowded. Then they eat things they would not normally eat and become vulnerable to various caterpillar diseases, none of which they seem to share with humans, and the local population level crashes. And so it goes, year after year. The animals don't have enough sense to practice birth control, so nature takes care of that for them.

Hyphantria cunea don't have conspicuous population boom-and-bust cycles. Their population levels, and thus the chance of their being perceived as a nuisance, depend largely on the weather. In the southern tier of States there are two or three generations a year, and the spring Webworms can and do eat enough spring leaves to affect summer harvests. Fall Webworms are harmless since the leaves they eat were about to dry out and drop off the bushes anyway.

Webworms that are close to pupation may be a little over an inch, sometimes a full 3 centimeters long. Tent caterpillars that are close to pupation are about two inches long, twice the size of Webworms. Their tents are bigger and more solid, too, and they live in bigger trees.

So how is confusion of these unrelated animals even possible? Because caterpillars are confusing little beasts. They're not big, strong, smart, or fast. They have to have something, for survival purposes. One thing they have is confusion. Hyphantria cunea is not very toxic to birds, snakes, lizards, or mice that might want to eat it. Dark H. cunea do, however, mimic M. americana.

And also we've not had the dark Webworms in this part of the world before.

When people aren't expecting dark Fall Webworms, even pictures of the little mimics can be confused with pictures of Tent Caterpillars. Especially if they're blurry cell phone photos.

This is the Eastern Tent Caterpillar. Basically a black animal at all stages of its caterpillar life, it shows a white stripe down the middle of the back of its second skin, and shows that halo of ginger fur in its final caterpillar skin. The blue spots are a Lasiocampid specialty. If you wanted to hasten the population bust without watching the caterpillars crawl around suffering, such that you wound the tent around a rake or a stick and dropped it into a fire, you'd notice the caterpillars giving off a strong, bitter scent and burning with a blue flame. They are peaceable little animals who show aggressive behavior only when they seem to be in great pain, and aren't capable of doing any harm when they do try to bite...but they can do some serious damage to predators that actually eat them.

And so a number of other caterpillars, each of whom normally has a different look, find a survival advantage in looking just a little bit more like tent caterpillars.

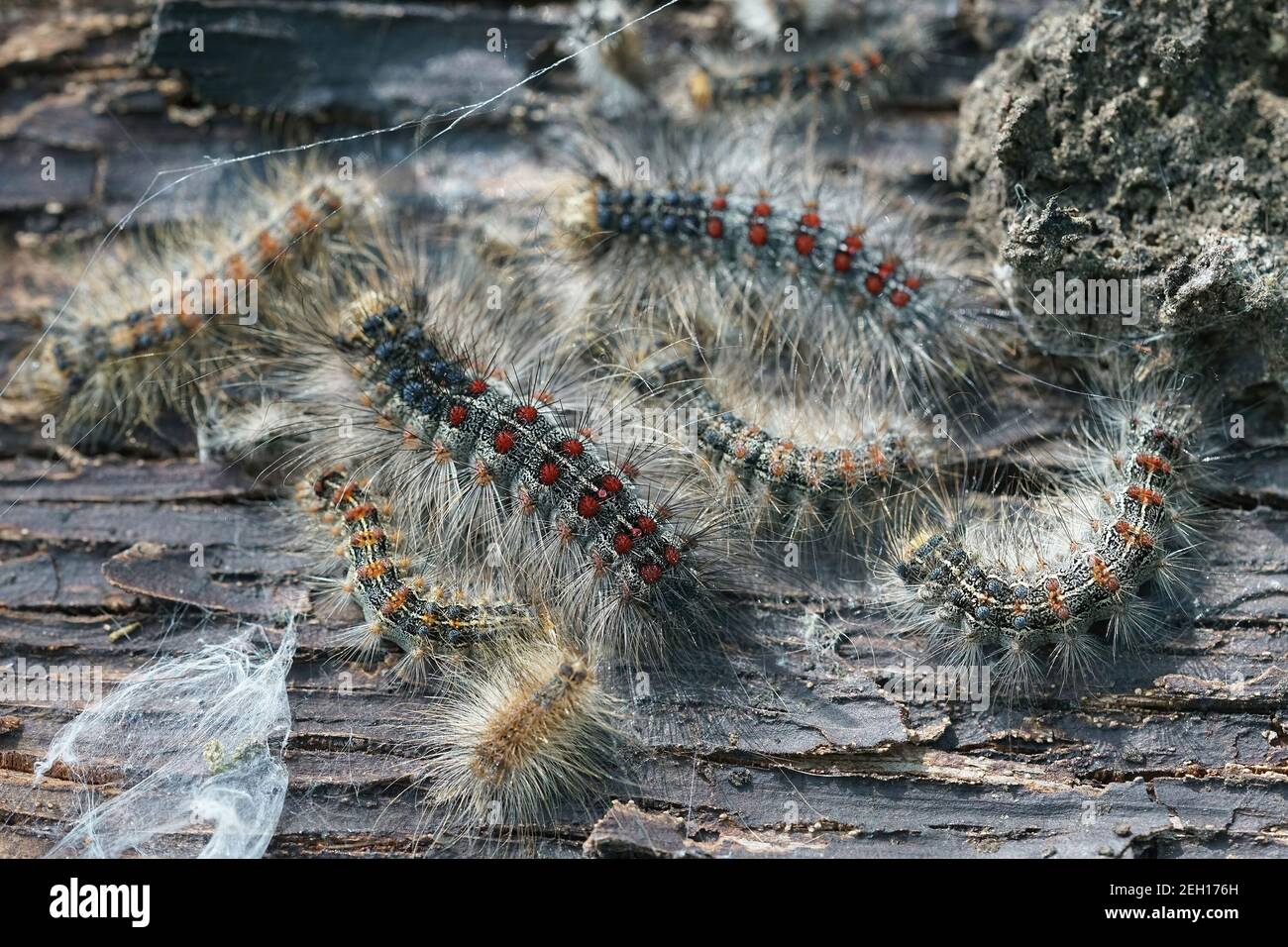

Here's a typical assortment of Dreaded Gyps, Lymantria dispar. Only during this presidential administration does anyone but me seem to have noticed that, although first and second instar caterpillars of this species are notorious hitchhikers, their traditional English name is a bit of an insult to the various European tribes who call themselves Gypsies. The best way to kill this pest species is to collect and destroy their eggs, which are laid in clumps that look like very small sponges with a lot of fur stuck to them. So the new name for the species is "spongy moths."

"Gypsy moths" had a variety of overtones. The "Gypsy step" in dancing is often explained as "holding onto your partner with only your eyes," and the caterpillars' big heads are often mistaken for big eyes. The Gypsy step is the most flirtatious part of the dance that includes it. Who wants to feel flirtatious about creepy-crawlies? Whereas...consider the overtones of "spongy." The caterpillars don't feel like sponges when touched--they're quite definitively "cold prickles"--but then there's sponging, or spunging, the detestable practice of hanging out at someone else's house in order to soak up food and drink, climate control, and other utilities which the "sponger" never invites the host to share at the sponger's house in return. Consider the sound of the word. If not "spongy," I think "sponger moth" is likely to catch on as a name for these unlovable creatures.

Anyway, what color is a normal gyp, or sponger? They start out black with white fur. Their second skins show the blue spots or warts on the thorax and red ones on the abdomen. Otherwise the skin usually looks black or grey, from a decent distance. If you get closer than most people want to get to the caterpillars you can see that the skin is speckled and can include light brown or green as well as black and grey speckles. Males, who will be less than half the size of their mates as moths, may be just an inch long and still look black when they pupate. Females, who spend more time being caterpillars and grow bigger, can develop final caterpillar skins in a variety of colors and patterns...

...and in places where Eastern Tent Caterpillars live, you'll find female gyps, or spongies, with blackish skin, ginger fur, and thin, pale imitations of the tent caterpillars' white dorsal stripe. These caterpillars are typically a little longer and considerably thicker than real Eastern Tent Caterpillars.

They imitate Eastern Tent Caterpillars' behavior, too, in a superficial way. Eastern Tent Caterpillars are very social insects, if they defoliate their tree they'll migrate as a family, with the eldest caterpillars leading the way (not that they seem to know where they're going) and the middle-sized ones nudging the youngest ones to follow the eldest one's trails. Their survival depends on the daily grooming sessions when they all congregate at their tent and pick dust and dirt out of each other's fur. Only in the last couple of days before they pupate do Eastern Tent Caterpillars get tired of hanging out with their siblings all the time, and wander around looking for attractive strangers to pupate beside. Spongeys have no such family ties; they disperse immediately after hatching, don't build tents, and don't groom one another. They do, however, learn that there are survival advantages in resting close together, on a mat of silk if possible, near a fork in a tree.

This is what everyone in Virginia and Tennessee knows Webworms look like:

...except in place where they might benefit from confusion with tent caterpillars. In addition to the yellow-green form we know so well, there's a fluffy white form and a dark drab form...and then there's this confusion-seeking form:

Though the Spongies have stiffer, scratchier hair than the Eastern Tent Caterpillars' and Webworms' soft fur, all three species are basically harmless little furballs. The caterpillar below is not harmless. Its bristling spines each pack about as much venom as a bee sting.

Its genus, Hemileuca, has been tentatively divided into about two dozen species. Nobody seems too positive about how distinct these species really are. Hemileuca can look very different while they all seem to be the same sort of thing; conspicuous differences can appear among litter mates. All the caterpillars look nasty, and they are, and several other little animals get some survival benefit from looking like Hemileuca larvae, a.k.a. stingingworms.

No comments:

Post a Comment