As luck would have it, the second butterfly species we're studying behind schedule is another madly popular species. Battus polydamas, the Polydamas or Gold-Rim Swallowtail, is popular because it's eye-catching and because it has a wide range. It's found around the southern edge of the United States and in Mexico, some Caribbean islands, Central America, and South America as far as Chile. Lots of places can claim it as a native species.

Photo donated to Wikipedia by Hectonichus. This individual butterfly came from the Niagara Falls Conservatory. Polydanas don't fly outdoors as far north as Niagara Falls, so it was probably reared indoors, probably on the Aristolochia vine which it's perching.

And Google aggravated this post. Everyone knows that commercial web sites want to be at the top of a Google search page. The goal is to deliver just enough information, often recycling information that is already widely known, to be classified as offering informative content along with the sales pitch or spyware "cookie." Serious researchers like the author of this unprecedented fact-packed post, therefore, want to scroll through lots of search results and read the handful of scientists' studies that have been published on the topic as well as the Wikipedia page, the "first articles" about the topic, and the pages dedicated to selling products related to the topic in some way. (For butterflies, that includes dead bodies and artistic renderings.) Advertisers have pleaded with Google to slow down the scrolling, to "force traffic" to the top-ranked sites. When I started researching this butterfly, Google seized up, refused to scroll smoothly through the first few pages at least, stuck on the second screen full of heavily advertised links with the pages for polydamas-inspired junk jewelry, and thereby drove me to finish the search on Yahoo. Yahoo's search algorithm proved to be less corrupted, delivering fewer duplicate links and more scientific studies/ Well...a manipulative web site is a dead web site. I expect Google to recover quickly after showing the advertisers how much traffic the effort to "force traffic" will cost them, but then again it's hard to overestimate the stupidity of people who want to be "gatekeepers" to human thought.

Google advertisers need to face reality. When people want information about butterflies, or anything else, we are not especially interested in junk jewelry. A blog post like this one might note as a sign of the butterfly's popularity that people do make and sell polydamas-inspired jewelry, but we're not going to buy or sell it. So, advertisers, kindly move your little pushcarts out of the way while we gather the fun facts that might conceivably make some reader, somewhere, recognize polydamas when person sees your junk jewelry in a store.

From a Google search...some butterflies are very obscure, and there may be only a handful of search results with two or three worthwhile links. For popular, well documented species like this one, from Google I'd expect about 200 results, 50 to 100 of which would be multiple links to the same few pages. From Yahoo I got 400 results with only about 20 duplicate links. Lots more links, photos, and videos to encourage butterfly enthusiasts and torture insect-phobics. More writing time, of course, also.

Of course, some of the links on which I clicked aren't scientific. One that's strictly for entertainment solemnly informs people that, if you see a black butterfly, you will have a sleepless night, probably because you're under stress, probably about money. Say what? I knew and loved black butterflies before I knew what money was, and the correlation between my seeing the black Swallowtails (and their mimics the Red-Spotted Purples) and my working at night is either zero or negative, I'm not sure which. The writer goes on to suggest that black butterflies might be a good omen of reconciliation among family members (a little push in the direction of niceness can't hurt, right?), or a sign that you're handling aging well (a "Barnum interpretation" if ever one was--I suppose, actually, four- and five-year-old children do handle aging well).

Just for laughs: https://www.ryanhart.org/black-butterfly-meaning/

Black butterflies aren't usually the ones that alight on people, and if they do, although a few black butterflies are males who like the taste of human sweat, what it's most likely to mean is that you've got something sweet and fruity on your clothes. If you cut off half-rounds of melon and eat them out of your hands, you're likely to attract black butterflies, along with less lovable animals such as ants. If you try eating a sweet tree-ripened Florida orange out of your hand, the way you might have learned to eat drier gas-ripened oranges shipped further north, that's another way to find any black butterflies who might be in the neighborhood. The general rule about Swallowtails is that females are pollinators who leave only flower pollen on your hand, while males are composters who may leave anything. How can you tell the males from the females? Black butterflies are more likely to be females, in many places, but in species like polydamas the males are black too. When a butterfly of any color alights on your hands, lets you admire its beauty for a few seconds, and then flits off, this is a sign that it's time to wash your hands.

Battus polydamas is so popular it's appeared on postage:

Linnaeus and his contemporaries liked naming species after heroes of ancient literature. Depending on which genre of ancient literature you prefer, Battus commemorates either an ancient king, from history, or a shepherd boy who basically did what employees are usually advised to do today and found that the ancient Greeks didn't appreciate the same pattern of behavior that modern employers do, from mythology.

What about Polydamas? The name is one of those two-part inventions that were popular in much of ancient Europe, from poly, many, and damas, to tame animals, or tame animals, or specifically cattle. In the Iliad Polydamas was a Trojan officer who urged his people not to attack Greece, but they did, and he fought bravely anyway--sort of like General Lee, except that Polydamas was killed in the battle. Another Polydamas in Greek literature was a legendary strongman, like Samson, said to have killed a lion with his bare hands, lifted a bull, and died trying to stop a rolling boulder.

Digitized image of Linnaeus' words from Lepiforum.org.

Battus polydamas was first described by Carolus Linnaeus himself. It's a large tropical butterfly, wingspan three to five inches. Though part of the Swallowtail "family" of butterfly species, it has no "swallowtails" on its hind wings. Males and females look alike; females are larger than males, on average, but individuals vary. Generally eggs are yellower, and caterpillars have fatter bodies and smaller tubercles, than philenor.

Polydamas is a low-altitude species, usually found near its host plants. Some of the Aristolochias it eats grow on relatively open land; others climb up tall trees, but polydamas is generally found in more "open" forests rather than dark, dense growth. Females spend most of their adult lives flying around vines, looking for the best places to lay eggs.

There are considered to be 22 subspecies--some common, some rare, some possibly extinct. The individual butterflies don't flit through their entire range; they tend to stay put and evolve distinct characteristics in each of their habitats. Some of the subspecies are, of course, better documented than others. They have different patterns of spots on the undersides of their wings; the subspecies lucayus, found in Florida and south Georgia, has similar markings on the upper and lower sides of its wings.. Wikipedia filled in photos for two of the subspecies below; I found a few more, but at least one subspecies, antiquus, never has been photographed, and probably never will be.

That antiquus ever existed is believed entirely upon the credibility of Dru Drury, an eighteenth century Englishman who drew clearly colored pictures of it. The thinking is that Drury drew pictures only of what he'd really seen, so if he drew a picture of a polydamas that didn't quite match any living butterfly since his time, there must once have been a subspecies that looked just like what Drury drew, and it must have gone extinct.

"

- †B. p. antiquus (Rothschild & Jordan, 1906) – Antigua (extinct)

- B. p. archidamas (Boisduval, 1836) – Chile

Photo by Lorenzo Vega. The site using this photo online, https://www.mhnconcepcion.gob.cl/noticias/mariposa-de-la-oreja-de-zorro

, uses archidamas and psittacus as synonyms.

, uses archidamas and psittacus as synonyms.

Here's a video showing one of these Chilean butterflies flitting and sipping:

- B. p. atahualpa Racheli & Pischedda, 1987 – Peru

Full description with large clear photos of museum specimens:

- B. p. cebriones (Dalman, 1823) - Martinique

- B. p. christopheranus (Hall, 1936) - Saint Kitts and Nevis, Montserrat (possibly extinct)

- B. p. cubensis (Dufrane, 1946) – Cuba (including Isla de la Juventud), Cayman Islands (Grand Cayman)

- B. p. dominicus (Rothschild & Jordan, 1906) – Dominica

- B. p. grenadensis (Hall, 1930) - Grenada, possibly southern Grenadines

Photo donated to Butterflies of America by Tom Bentley, who notes that this rather worn individual was found on Tobago.

- B. p. jamaicensis (Rothschild & Jordan, 1906) – Jamaica

- B. p. lucayus (Rothschild & Jordan, 1906) – Florida, Bahamas

- B. p. lucianus (Rothschild & Jordan, 1906) – St. Lucia (possibly extinct)

- B. p. neodamas (Lucas, 1852) – Guadeloupe

- B. p. peruanus (Fuchs, 1954) – Peru

- B. p. polycrates (Hopffer, 1865) – Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic)

Photo donated to butterfliesofamerica.org by Sheridan Coffey.

- B. p. polydamas (Linnaeus, 1758) – tropical Central and South America

- B. p. psittacus (Molina, 1782) – Chile, Argentina

Photo donated to Inaturalist.org by Sebastianvanzulli, who notes that it was taken in Chile in November.

- B. p. renani Lamas, 1998 – Peru

- B. p. streckerianus (Honrath, 1884) – Peru

Photo by Dbeadle, who holds a copyright and wants payment if his photo is used for payment. Many of the fair-use photos here are subject to copyright if used in paid work. That's why the cost of publishing this series as a printed book would be prohibitive and why I've opted for "personal use" on my personal blog, primarily for the benefit of The Nephews, instead. You may print off your own copies, but don't sell them.

- B. p. thyamus (Rothschild & Jordan, 1906) – Puerto Rico (including Culebra), Virgin Islands

- B. p. vincentius (Rothschild & Jordan, 1906) - Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

"

Although some subspecies have probably gone extinct, the species as a whole is considered to be "of least concern." The distinctive mutations that produce subspecies may or may not recur.

Trying to attract polydamas to the garden will generate controversy if you're guided by the video linked below. The young man proudly points out dozens of eggs and tiny caterpillars on the exotic pipevine, Aristolochia grandiflora. It has a much larger and stronger-smelling flower than the native Aristolochias the other butterflies in the Troidini group can eat. As the man observes, the big, dark red flower on grandiflora smells like carrion. It looks like dead meat, too; to my eyes it's not beautiful at all. He doesn't find any of the full-sized caterpillars. That may be because the cool weather he mentions has simply encouraged all those eggs and baby caterpillars to hatch a week later than he expected. However, exotic Aristolochias will attract other insects (not all of them Swallowtail butterflies) that eat native Aristolochias, and this confusion may lead to sick or dead native insects.

According to https://butterfly-fun-facts.com/gold-rim-butterfly-battus-polydamas/, both Battus species can eat the Aristolochia species fimbriata, pandurata, and trilobata.

As bugoftheweek.com observes...

Members of the pipevine family, such as the strange pelican flower vine, are too toxic for some Battus species to consume as larvae, but not so for rugged caterpillars of the Polydamas swallowtail.

"

The member of the pipevine family that's too toxic for the other Troidini is A. elegans, which looks similar to A. grandiflora. Battus polydamas' various subspecies eat a wide variety of Aristolochias and can live on species that aren't harmful to Battus philenor or other native wildlife.

This post explains (in Portuguese; thanks to the pan-Europeanism of scientific jargon, it can be read as if it were Spanish) how the Aristolochias depend on Swallowtails as pollinators:

Aristolochic acid is not the caterpillars' only defense. Although it's toxic, at least three caterpillar-eating animals--carpenter ants, assassin bugs, and domestic chickens--do not immediately notice its toxicity and will eat things contaminated with aristolochic acid that otherwise taste good to them. Chickens and carpenter ants will eat another young, small polydamas caterpillar after having eaten one, but not another full-sized one. Other biochemicals make the older caterpillars even more disgusting, such that chickens and carpenter ants will leave them alone. Assassin bugs will go after even full-sized caterpillars. No lifeform's natural defense is perfect.

Although it's usually bigger and looks completely different from the typical United States specimen of Battus philenor, some of the South American subspecies of philenor are larger and can look more like polydamas, and crossbreeding is possible, though very rare, The "Coeruloaureus" butterfly ("sky-blue-and-gold") is one of the few hybrid animals known to occur in nature without human help. If you see one, snap photos and save them to show your grandchildren. Somebody offered a dead crossbreed for sale, claiming that it was "probably unique." This web site, of course, recommends never paying for dead butterflies or parts thereof. We should not encourage desperate students to contribute to local population or subspecies extinction.

In Chile, for reasons that continue to baffle scientists, the subspecies archidamas and/or psittacus and their host plant, Aristolochia chilensis, go through regular population irruptions. When the population reaches a critical density, every few years, the butterflies apparently attempt to migrate across the ocean. This migration is doomed. Though individual butterflies may be bigger than some Monarch or Mourning Cloak butterflies, they are still only Swallowtails. They fly a short distance out to sea, then collapse into the water and may wash up on beaches if the tide is coming in. While this lemming-like behavior clearly functions to regulate population, humans will probably never know whether the butterflies' last thoughts are that better food is available elsewhere or that they're escaping predators...

People who had heard that some of the Aristolochias are used as medicine, but observed that the tropical species in this plant genus tend to be too toxic for medical use, have tried extracting the medicinal properties of aristolochic acid from the caterpillars. The caterpillars were pickled in rum, which was then given to patients. The brew was sold under the name "Chiniy." However, its use and sale is now banned as likely to do more harm than good. In addition to its unpleasantly overstimulating immediate side effects, which range from heart palpitations and nausea to spontaneous abortion with hemorrhaging, aristolochic acid is known to damage the kidneys and believed to contribute to the growth of cancer in humans.

Perhaps the surplus butterflies in Chile could be studied for clues that might help humans resist cancer? Valeria Palma thinks so:

Researchers have found it possible to rear and breed these butterflies on synthetic food. The caterpillars do seem to have some biochemical ability to "detoxify" aristolochic acid, although this study emphasizes that much remains to be learned about whether this process will ever be useful to humans:

Other studies of the biochemistry of Troidine digestion and metabolism have been done. Some are old enough to be available online free of charge; some are new enough that only abstracts or first pages are available free of charge. Nothing of great importance to medical science has been learned yet, but it's a topic medical students might want to follow.

A detailed study of the life cycle of Battus polydamas cubensis is free for the downloading from

This quick study shows how to tell polydamas from philenor. Briefly: eggs and caterpillars are easy to distinguish, pupae are not, adult butterflies are hard to confuse.

Like many other Swallowtails, these butterflies catch the eye by being active and moving fast as well as by being large and colorful. Males show off their energy by trying to fly higher and faster than one another or than females they are trying to impress. Fortunately for the males, egg-loaded females seem easily impressed. They mate back to back, but sometimes one butterfly gently enfolds the other's wings between its own. In available photos, the female seems to embrace the male, which may serve the purpose of checking his scent-releasing behavior. While flying around the female to show off, the male polydamas releases the distinctive odor of his species. His scent folds are only about a millimeter across. That's enough to prove his species identity. Female polydamas like Aristolochia and Lantana flowers, which also smell rather off-putting to humans, and they probably like their mates too--but enough is enough of anything.

Although the size difference is not necessarily great, butterflies are light. If a couple are disturbed during their moments together, the female can carry the male to a more private place. One of the few things these butterflies do that stop them fanning and fluttering their wings is snogging, sometimes for hours.

Eggs are often laid in small groups. While many large caterpillars need a whole plant to themselves, in the tropics Aristolochia vines grow fast enough to survive having their leaves stripped by a family of very hungry caterpillars. Females seem to be in a hurry to lay their eggs, and can afford to drop ten or fifteen in the same place, a luxury many Swallowtails don't share. They look for tiny, fresh, new leaves and stem ends. By the time the caterpillars hatch, the fast-growing leaves will be big enough to hold them and still soft enough for baby caterpillars to digest.

The butterflies have an imperfect instinctive sense of which host plants are best for their young. As noted above, this is not the most survival-intelligent animal on Earth. Probably feeling some urgency to unload fast-developing eggs, they may place eggs on species of Aristolochia that will not adequately feed their caterpillars. They do recognize and prefer the optimal species, but so do the caterpillars. One can imagine a butterfly rationalizing to herself--if butterflies think so far ahead--that the caterpillars can live on an inferior host plant long enough to recognize its inferiority and crawl off to find better food...Such, of course, is not always or even often the case. A malnourished caterpillar's chance of finding better food is even lower than a healthy one's. Older caterpillars do, however, move out on their own and sometimes find better host plants than they left.

The VolusiaNaturalist blog has a full photo essay of the life cycle of polydamas lucayas, but the close-up of an egg being laid is probably unique.

Like other eggs of butterflies in this genus, the eggs look like little round beads, textured with drops of aristolochic acid that discourage predators. The eggs shown below were about to hatch.

The Dauphins' photo essay shows the life of an individual butterfly, probably Battus polydamas polydamas, reared in captivity near the Rio Grande:

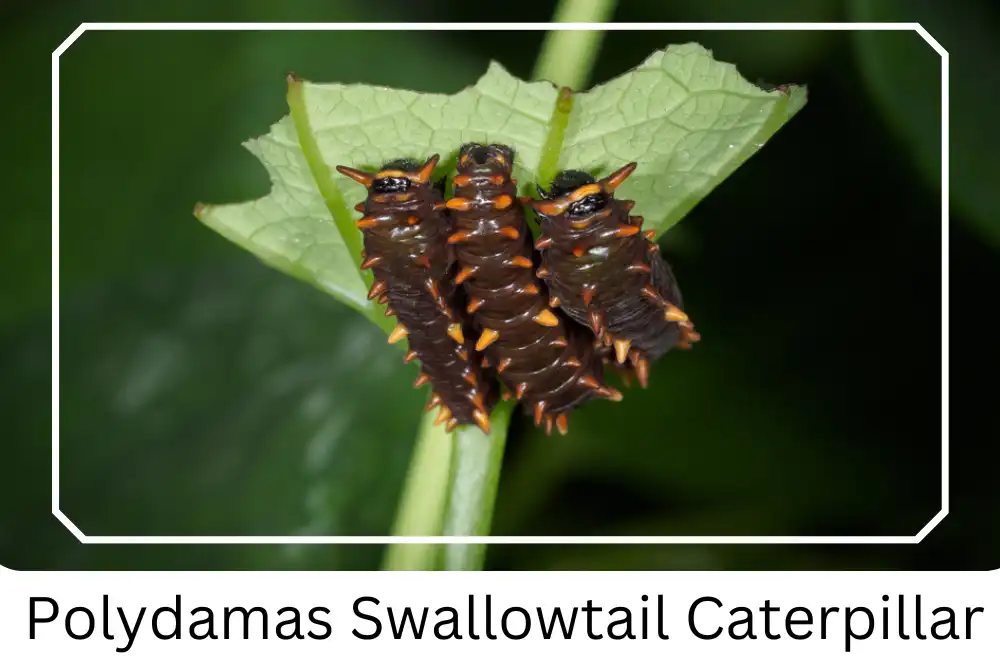

Although they eat their own shed skins, they seem to hatch with enough social instinct not to try to eat their siblings' skins. While they're small enough to share leaves, they are one of several butterfly species in which the caterpillars instinctively line up in a row. Touching sides may feel pleasant to the caterpillars; it also increases the chance that predators may mistake them for something harder to eat. As they grow bigger, they separate so that each one can eat a leaf of its own. Like all Aristolochia eaters, these caterpillars have three other defenses: they are toxic and apparently taste nasty to most creatures that eat them, they are creatively ugly, and they smell like their host plants' flowers. Swallowtail caterpillars can aggressively release a whiff of carrion by displaying their osmeteria, the "stink horns" at the back of the head that come out when the caterpillars feel threatened.

The chemicals in the odors have been analyzed, and this species' osmeterium has been dissected under an electron microscope.

Caterpillars in groups are more likely to evert the osmeterium and merely stink at researchers who pester them. Caterpillars feeding alone are more likely to thrash their heads about in a threat display (they can't bite humans hard enough to do more than vent their emotions), during which the osmeterium may also be everted. See Week 1's joke about the benefits and costs of being en entomologist.

Photo donated anonymously to butterflyidentification.com, which states that these caterpillars mature through only four instars (changes of skin) and spend about three weeks being caterpillars. Other sources mention that while some caterpillars can pupate after four larval instars, others go through five, six, or even seven caterpillar skins before pupating. In sexually dimorphic moth and butterfly species, where the female is larger or only the male has wings, caterpillars of one sex may take an extra instar to develop, but the purpose of polydamas' range of variation is unclear. Since each additional instar lasts five or six more days, and siblings thus pupate and eclose ("hatch" from the pupa as adults) at different times, there may be an overall survival advantage in allowing some individuals to pupate through periods of less favorable weather, or allowing generations to overlap may promote genetic diversity.

Cisternas, Rios, et al., studying these caterpillars, suggest that longer juvenile lives may be normal for the species, and touch may speed up their development. As with philenor, the mother butterfly may lay her first few eggs in bunches, later eggs by ones and twos. Caterpillars who grow up alone and are undisturbed may mature through more instars, while those who grow up in groups and/or are disturbed may find themselves rushing through adolescence to reproduce earlier. The size of pupae did not seem much affected by the time the caterpillars took to reach pupation. If pupating within three weeks after hatching, going through only four instars, is normal for the species, then more instars and another week or two as caterpillars seem to add nothing to species survival. If, on the other hand, spending five or six weeks as caterpillars is normal for polydamas, the ability to reach "mature caterpillar" size and pupate as early as eighteen days after hatching is a remarkable adaptation. Passing through more vulnerable life stages more quickly would presumably allow more individuals to mature and reproduce. The entire life cycle can be over in forty days or fewer, or can last for several months if the individual matures slowly and pupates through a cool season.(It does not survive in places where temperatures drop below freezing.)

However, being closer to one another increases vulnerability to internal parasites. Battus polydamas can be parasitized by microorganisms in the genus Perissocentrus. So, a mix of faster-maturing, "chummy" caterpillars and slower-maturing, solitary caterpillars may provide the optimal balance for species survival. Interestingly, both "good touch," the presumably reassuring sensation of being close to siblings, and "bad touch," being harassed by potential predators (from the caterpillars' point of view, humans fondling their soft little horns undoubtedly seem like predators), seem to stimulate accelerated growth.

The caterpillars' ability to speed up their growing time depends partly on diet; this study found that, between caterpillars reared on only one of the Aristolochia vines that grow in Chile and caterpillars given a choice of both food species, the caterpillars given a choice pupated earlier, were more likely to survive, and also--for whatever this may be worth to them--had larger heads.

All this may have something to do with one of the anomalous facts about these butterflies. The usual rule is that the length of the caterpillar is close to the wingspan of the butterfly or moth, but several species are exceptions. Polydamas is one; while adults' wingspans are almost always over three inches, the stubby little caterpillars grow only a little over two inches long.

Diet shapes the caterpillars' development but its precise effects remain unclear. They can eat flowers as well as leaves of their host plant; they tend to strip plants, which then grow back quickly.

Pinto, Troncoso, et al. found that a diet higher in aristolochic acids consistently produced bigger caterpillars with a lower mortality rate. They mention their research subjects' sixth instars but did not study whether extra instars are promoted by a richer diet, or how or whether extra instars may benefit individuals or the species.

Gonzalez-/Tauber et al. speculate that overall climate warming might benefit Battus polydamas archidamas:

(Though archidamas has sometimes been regarded as a separate species, it's also often regarded as the same subspecies as psicttacus.)

Isis Meri Medri has posted a video of a caterpillar tidily eating its shed skin. Not for the squeamish.

In the fourth instar the tubercles (warts) behind the head grow longer and look like little horns, but don't become tentacles the caterpillar can use to find the freshest part of a leaf, as philenor does. Polydamas caterpillars grow bigger than philenor and have shorter "horns." The horns can be moved and can be turned down but are not tapped along the surface as the animals walk.

In addition to the "horns" one pair of tubercles on the side, toward the end of the caterpillar, grow long enough to be moved independently. This video shows these tubercles twitching aimlessly, apparently as part of the caterpillar's body movements as it nibbles off the end of the plant. Do they help the caterpillar find tender leaves by tapping the surface on which it walks, as philenor's tentacles do?

As the caterpillar crawls over the researcher's hand in this video, it lifts its head and looks about every few steps, while the extended tubercles toward the rear tap the surface of the hand.

Caterpillars' colors can vary. In lucayus most caterpillars are black with orange-tipped warts, and the lighter-colored caterpillars are lighter brown rather than bright red. However, they have a pattern of striation, which can be hard to see on dark brown or black individuals. This individual from Costa Rica is purple, white, and gold.:

A white morph is documented in Peru in this study (written in Spanish only): It can be cream-colored with beautiful, subtle streaks of reddish brown, or even pink with streaks of red.

Ecos del Bosque notes that this purple-white-and-gold individual was found on a citrus tree not far from an Aristolochia vine. They can't live on citrus leaves but may, like philenor, intentionally leave the plants on which they are feeding and rest somewhere else, where they think predators won't look for them. Like the adults, fourth-instar and older caterpillars can find their way back to their food plants by scent.

A blog dedicated to showing off unusual "smartphone" photos shows the caterpillar approaching the bizarre flower of Aristolochia chilensis:

The pupa can be greenish or brownish and looks as if it might be a dead leaf, at least until the butterfly inside starts to show through. Pupation often lasts less than three weeks.

Natural selection favors pupae of different colors in different climate conditions, as the green ones are better camouflaged against green plants, the brown ones against dry ground. This creates another balance of benefits between traits for Chilean polydamas, whose host plants live in places that become desertlike for part of the year.

Adult butterflies are usually thought to fly for two weeks or less, though some sources think they may occasionally live longer. At the ends of its range, this species has two or three distinct generations each year--April to November in the United States, September to March in Chile. Near the equator it is active all year, with overlapping generations.

No comments:

Post a Comment