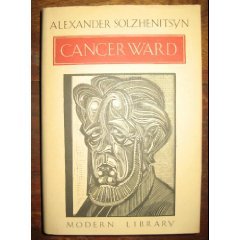

Title: Cancer Ward

Author: Alexander Solzhenitsyn (also spelled Alexandr, Aleksandr, etc.)

Date: 1968

Publisher: Farrar Straus Giroux (1969), Random House (1983), and other editions

ISBN: 0-394-60499-7 (Random House Modern Library, the one I'm looking at as I type)

Length: 536 pages

Quote: "But affairs of state did not succeed in diverting him or cheering him up either. There was a stabbing pain under his neck."

Rakovyi Korpus, soon to be translated as Cancer Ward, might have been considered an undistinguished novel if it hadn't got Solzhenitsyn into so much trouble with the thin-skinned Soviet authorities. It contrasts two cancer patients, a "successful" civil servant, husband and father, Rusanov, and a young, tough prisoner, Kostoglotov, who don't like each other much, as they endure treatment and achieve remission.

A lot of suffering goes on. Anyone who's spent time on a real cancer ward will recognize that the suffering has been considerably toned down just to make their story readable. Body parts, body fluids, painful symptoms and treatments, are mentioned liberally, but in nothing like the proportion to ideas, feelings, and stories in which they're mentioned in a real hospital. We see characters sick, crying, delirious; we don't see them howling in agony, or dying, as might be expected in a real hospital. What makes this a novel is that they have ideas, and families, and future plans.

What made it a controversial novel is that, although they're good patriotic citizens of the Soviet Union, they are...human. Rusanov thinks his position in the government ought to entitle him to better service than others get, or than he gets, even while he's living in fear that a past political mistake may be exposed. Other characters have been "exiled" or imprisoned merely because they belonged to ethnic minority groups. All the characters are loyal Soviets, yet the Soviet system isn't serving any of them really well.

"Telling the people the truth doesn't mean telling them the bad things," proclaims Alla, the "smart" daughter whose visit cheers the ward for an hour. "Where does this false demand for so-called harsh truth come from?...Our literature ought to be wholly festive."

Of course this is not the most encouraging thing Alla has come to tell the patients; what she says that really lifts her father's spirits has been more private--"It's out of the question to get someone on a charge of giving false evidence now. Rodichev won't utter a squeak."

Solzhenitsyn was, like his characters, a good patriotic Soviet at the time of writing, but he wasn't Alla. He seems to have more sympathy with the young man Alla is shouting down with her speech about making literature "wholly festive." Domka, like his author, prefers "sincerity." It's impossible to read Cancer Ward without feeling a sense of the author's sincere compassion...and yet, how could he express that compassion without showing how the totalitarian government made Alla the liar and her father the coward they are?

And what about the end of the story? "The hero renounces life," one critic summed it up, but does he? Does he really, necessarily, even renounce love? I can't claim to understand the novel better than readers of the author's own nationality and generation, but must it be understood as hopelessly as the critic Kerbabaev claims? Solzhenitsyn said it was a story in which "life conquers death." He never says straight out, "With just a little liberalization of government policy, Oleg and Vera could marry." He may not have meant to say that...but it's what his story brings to this American reader's mind.

That it aroused opposition in the U.S.S.R. naturally gave Cancer Ward, and Ivan Denisovich also, an audience in the English-speaking countries. Not only was it translated into English in the year of publication; the English translation was even rushed to press in parts, so that, although the novel fits into one average-sized volume, it's been printed as a two-volume set. At the same time, the mere fact that a book was allowed to filter through the "Iron Curtain" made it somewhat suspect. Cancer Ward was in print, and was in some public libraries, when I was growing up; it wasn't a huge seller, nor can I remember anyone ever suggesting that I ought to read it--nor did I read it before age fifty.

also, an audience in the English-speaking countries. Not only was it translated into English in the year of publication; the English translation was even rushed to press in parts, so that, although the novel fits into one average-sized volume, it's been printed as a two-volume set. At the same time, the mere fact that a book was allowed to filter through the "Iron Curtain" made it somewhat suspect. Cancer Ward was in print, and was in some public libraries, when I was growing up; it wasn't a huge seller, nor can I remember anyone ever suggesting that I ought to read it--nor did I read it before age fifty.

So, who should read it? Mature adults only, for sure. I wouldn't have liked or appreciated it even at thirty-nine--before becoming a cancer widow. It's not at all a bawdy story, and yet the possibility of a "life conquers death" reading depends on the reader's understanding of middle-aged sexuality. Teenagers (how old was Kerbabaev?) just won't understand. Additionally, as stories about cancer wards go, this one is clean, wholesome, and hopeful, but you have to have spent time in a cancer ward to see that.

Now a note on prices and editions. At the top of this review I've pasted two graphics. One (bigger picture, smaller book) shows a cheap paperback edition that's likely to be available indefinitely at prices that allow me to offer it for $5 per copy + $5 per package + $1 per online payment. The other shows a much nicer library edition, which is the one I physically own at the time of writing; if online shoppers want this or another "nice" hardcover copy, I may have to charge $10 per copy. Solzhenitsyn no longer has any use for either $1 or $1.50, so if you can find a better price for this book, feel free to buy something else from this web site.

No comments:

Post a Comment