Merry Christmas, Gentle Readers!

A Fair Trade Book

Title: Whence Came a Prince

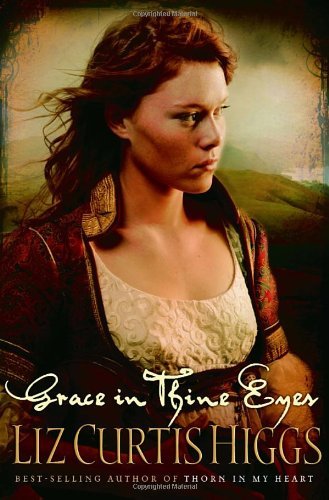

Or you could buy the four-book series where this book is volume three, photograph showing volume four:

Author:

Liz Curtis Higgs

Author's web page (Wordpress, unfortunately): http://www.lizcurtishiggs.com/

Date:

2005

Publisher:

Random House

ISBN:

1-57856-128-0

Length:

537 pages of text plus notes, glossary, and discussion questions

Quote: “If

you find even a single coin of your gold in our possession, I will run my sword

through the heart of the one who stole it.”

Having

recast many Bible stories as contemporary short stories, Liz Curtis Higgs was

invited to try historical novels: the legal loopholes that allowed greedy

Laban to marry both of his daughters to the same man at the same time would

also have been just within the bounds of possibility in eighteenth-century

Scotland. Hence the series that began with Thorn

in My Heart, in which the one thing that nags at the reader’s suspension of

disbelief is that Jamie McKie and his wives (and first cousins) Rose and Leana

are reenacting the Bible story of Jacob, Rachel, and Leah, and, though members

in good standing of the Church of Scotland, none of them notices.

Thorn in My Heart  was about Leana’s

falling in love with her cousin. Fair

was about Leana’s

falling in love with her cousin. Fair  Is

the Rose was about Rose’s falling in love with the same boy. Whence Came a Prince is mostly Jamie’s

story, about separating himself from his money-grubbing uncle Lachlan and going

home to inherit his father’s estate, becoming a man and a father and a Scottish

“laird.”

Is

the Rose was about Rose’s falling in love with the same boy. Whence Came a Prince is mostly Jamie’s

story, about separating himself from his money-grubbing uncle Lachlan and going

home to inherit his father’s estate, becoming a man and a father and a Scottish

“laird.”

In the

Bible Jacob, Leah, and Rachel lived in their bigamous and incestuous

relationship for most of twenty years; Jacob worked seven years to earn each

sister’s dowry and a few more years for shares of the profits. During this time

each sister, trying to produce more babies and thus qualify for a bigger share

of the family’s wealth, also ordered a trusted maidservant to make a few babies

with Jacob, which babies were “born on the knees” of the rightful wife and

recognized as adopted children of hers. At least twelve healthy babies were

born—eleven sons and a daughter—and some speculate that these four women may

have produced other children, as well, whose names were not recorded because

they weren’t heirs. Only at the end of this time did the family move, with poor

baby-craving Rachel dying in childbirth, giving birth to the twelfth and last

(documented) son, along the way.

In some

languages time is counted not by full years but by seasons. In the other books

of the Bible time is clearly counted in full years. In Genesis, however, people

seem to age at exactly twice the normal rate. Some scholars, considering the

ages at which Abraham and his descendants do various things in Genesis,

speculate that the word later used to mean years once meant seasons, of which

there were typically two in a year. It’s pertinent to mention this because, if

the word used to measure age is translated “years” as it is in most English

Bibles, Jacob had no relationships with women prior to those two decades of

frenetic baby-breeding, and those four young ladies were fighting over his

attention, when he was between the ages of seventy

and ninety. (And he and Leah lived many years after that.)

The Bible

suggests that Jacob was considered to have matured slowly because he was a bit

of a “Mama’s boy.” That was why his father preferred his brother Esau, who

was history’s first recorded “redneck,” with red hair all over, a hasty temper,

little sense of responsibility, no thought of the future, little spiritual

intelligence and apparently no outstanding quantity of practical intelligence,

but at least Esau was bold and tough. Old Isaac, a gentle man, relished Esau’s

hunting adventures as much as he did the game Esau brought home.

The

brothers were twins, though far from identical. Smooth-skinned,

slick-talking, clever Jacob was a scientific farmer who studied different ways

to breed livestock for the traits he wanted, but had to give God the credit for

his successes in breeding for minority traits while working for shares of

Laban’s profits. He just knew (and so did his mother know) that he was better

qualified to inherit the bulk of the estate and the social status that went

with it, but since Esau was born first, Jacob had to play tricks on both his

father and his brother to become the heir. After playing these tricks he worked

on his uncle’s estate to give the righteous indignation time to cool off.

Esau’s threat to kill Jacob might have been idle drunken bluster. Then again it

might not. Both brothers were wealthy ranchers who employed a lot of young men

to supervise their herds of animals. Herdsmen had to be prepared to fight off

predators, so if Esau seriously wanted to kill Jacob, each brother was the head

of a small army; the “fight” for the estate could have become gory. It didn’t,

because Jacob’s “wrestling with God” gave him the grace of humility. As adults

Jacob and Esau don’t seem ever to have been close, but they managed to coexist, with Jacob as head of the clan.

In Hebrew

sar, a prince, or sarah, a princess, are the noun forms

that go with a verb, yisar, meaning

“he fights or wrestles.” Thus when Jacob reached his full status as heir, sheikh, patriarch, he received the title

“Israel,” which can be understood to mean either “prince of God” or “he

wrestles with God.” (In youth his grandmother, Sarah, had apparently earned a

pejorative nickname, Sarai, which ought logically to have meant “my princess”

but seems to have been understood to mean “quarrelsome.”)

Higgs’

attempt to re-create a man’s spiritual coming-of-age is still told primarily

through the eyes of his wife. For me this gives the story more credibility

(Higgs has done most research on the home lives and women’s work of

eighteenth-century Scotland, which are of course what the “pioneers” brought to

the Eastern States). For men, does it inherently, inevitably, keep a story told

by a woman, for women, mostly from a woman’s point of view, somewhat off the

mark? Possibly. Would a practical,

even scientific man like Jacob tell a story of spiritual maturation in more

detail than Whence Came a Prince?

What the Bible tells us about Jacob’s spiritual journey consists of a few

sketchy dreams he shared with his family, plus the record of how people remembered his everyday dealings with other

people.

So…eighteenth-century

Scotland is not the ancient Middle East. Jamie McKie matures into a “bonnet

laird,” not technically a prince…but Jamie McKie is still only in his twenties,

and he’s still Leana’s Prince Charming. And Higgs spares us the murky business

with the maidservants, although the names of Eliza and Annabel seem chosen as

being as close as eighteenth-century Scottish names got to Zilpah and

Bilhah. Jamie, Rose, and Leana are still

cousins, but at least, after Rose dies, only two people are sharing a bed.

I suspect

that most people who enjoy Whence Came a

Prince will enjoy it for the social history. Leana is still using the herbs

and recipes, guided by the superstitions, reciting the poems and singing the

songs, and dressing everybody in the clothes, of eighteenth-century Scotland.

If these novels are on the long side, that does them no harm; anyone who’s read

the Bible knows how the story has to come out (although, as noted, Higgs has

taken some liberties) so readers are lingering for the atmosphere, quaint yet

somehow homelike, of our great-great-great-grandmothers’ time. We want to know

when and how people used the herb called lady’s-mantle, what lullabies parents

sang to babies, what remedies herdsmen applied to injured sheep. Higgs tells

readers all these things, and evidently, judging by the popularity of this

series, they relish every bit of it.

No comments:

Post a Comment